During the rise of America’s auto industry, Detroit, Michigan – the Motor City itself – was also known as a center for popular music. Jazz acts like Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis – and later on – Rockers like the Velvet Underground, Detroit’s own MC5 and The Stooges were all regular features at the city’s legendary ballrooms.

Built in the 1920s with a distinct Aztec theme, the Vanity Ballroom is at the heart of the Jefferson-Chalmers, a working class African-American neighborhood on Detroit’s lower east side.

But, as the fortunes of Detroit declined, so did those of the Vanity and the neighborhood around it. The ballroom has been abandoned for about 30 years.

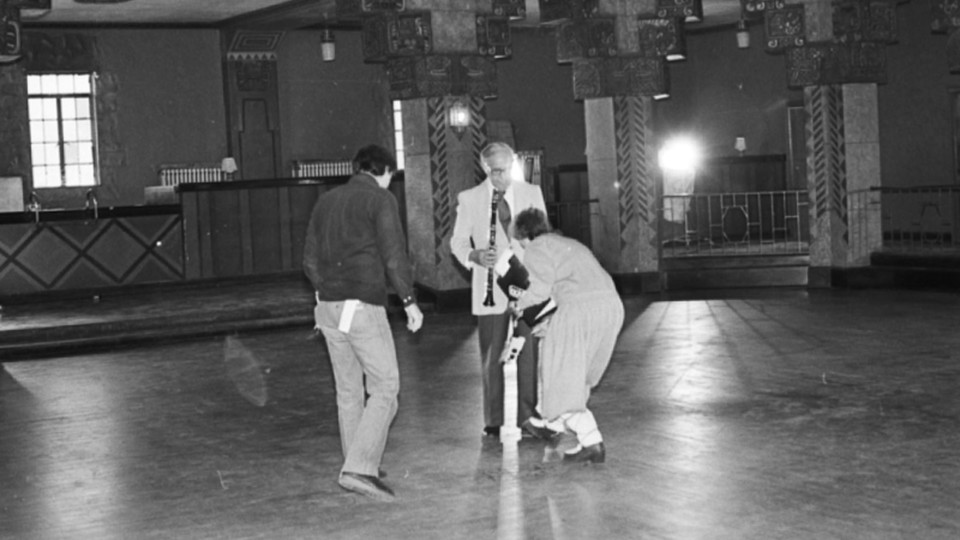

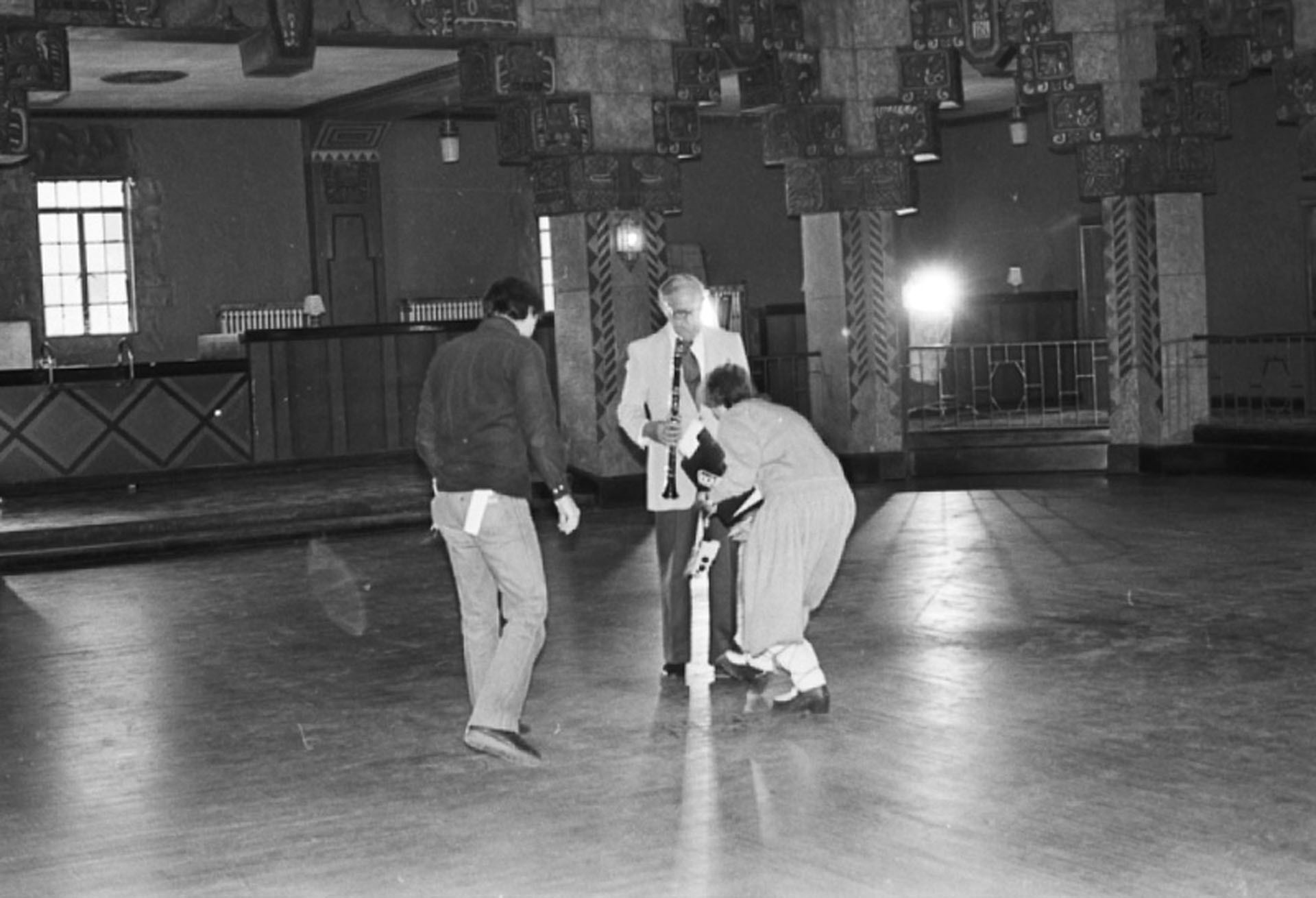

Photos from the Vanity Ballroom

Click the picture below for more photos from this feature.

Joshua Elling is Executive Director for Jefferson East, Inc., a non-profit working to revitalize neighborhoods along the Detroit’s east side.

“Back during the automotive boom, when Detroit had 2 million people, this was the center of jazz and blues entertainment for the Lower East Side of Detroit. And as the automotive jobs left – as people moved to the suburbs – there was less of a demand. And these buildings fell in disrepair.”

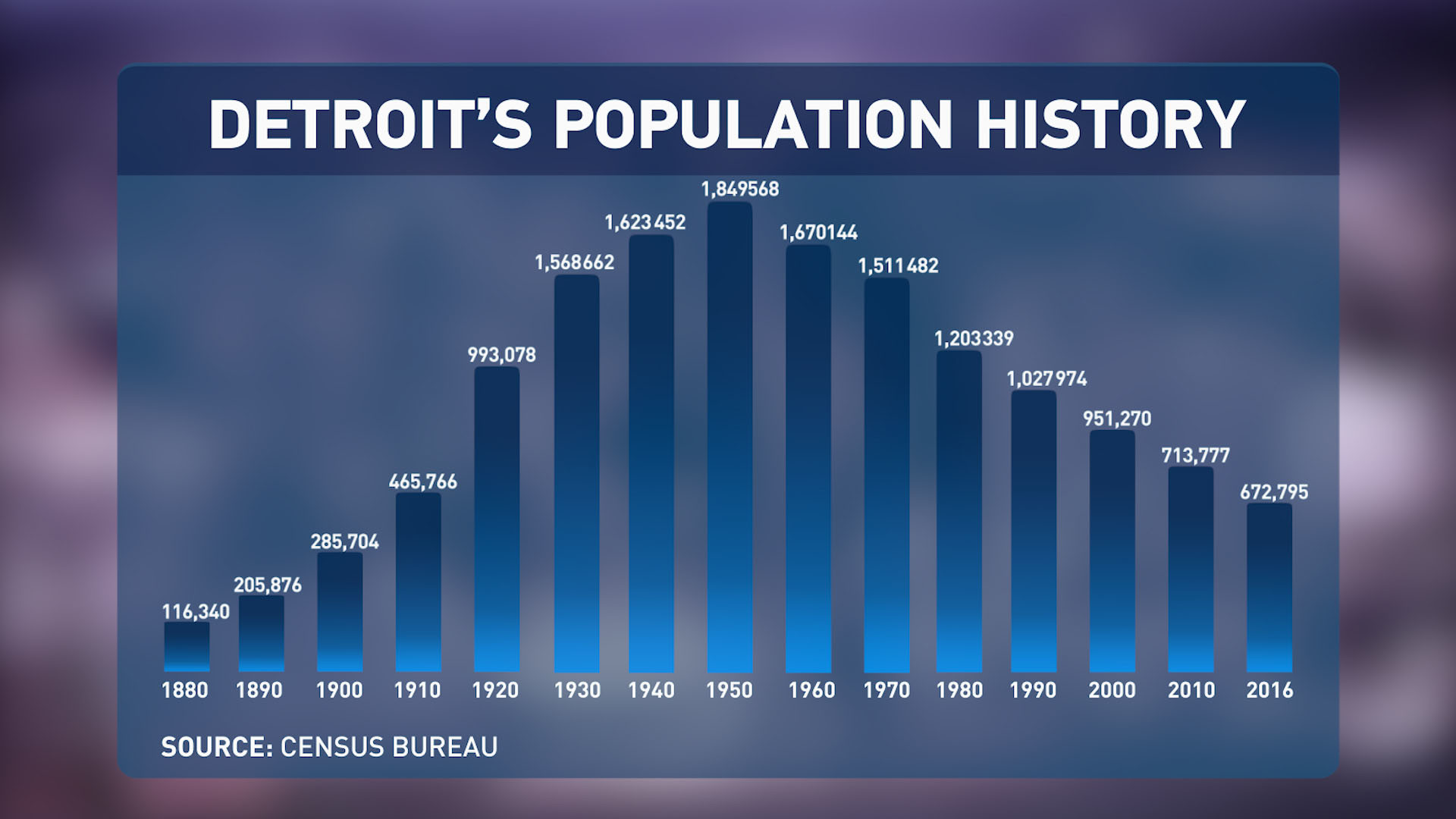

Since 1950, the peak of the auto boom, almost 1.2 million residents have left Detroit. That’s a loss of about 64 percent.

“You still have these pockets of incredibly low density, where you can see the abandonment of Detroit over the years manifest itself,” said Elling. “So it really is still a mixed tapestry.”

As part of their model, Jefferson East acquires historic buildings on Detroit’s East side. Then, working with other partners, restores them for affordable housing, and community driven business.

Local chef Gary Alma is building out his first restaurant in the Kresge Five and Dime building, built in the 1930s.

In addition to restoring old buildings, another priority has been making sure new business owners coming in have what they need to find success.

At the Kresge building, a former five and dime acquired by Jefferson East, local chef Gary Alma is working to build out his first restaurant.

“Gary had to put together stacks of $300,000 to $500,000 to finance their build out,” Elling said. “But, because they have a nonprofit partner that owns the building, they’re much more likely to receive those resources than they would be otherwise.”

In Detroit, as with other cities in the U.S., the restoration of historical buildings can qualify for:

• Local, state and federal development grants, such as Michigan’s Motor City Match.

• Tax breaks, like the Federal Historic Tax Credit.

Buildings with historical status also encourage philanthropic donations, as well as bank financing. This stacking of incentives can be crucial for aging cities like Detroit.

The Kresge building, a former five and dime built in the 1930s, is being renovated to host Gary Alma’s new restaurant and Jefferson East’s new offices.

Detroit has over 300,000 existing buildings. Ninety-seven percent of those are 50 years old, or older. In fact, two thirds of them were built before World War II.

“In terms of a city that’s ripe for reuse and reinvention, Detroit probably has more opportunity than any other city in the country,” says David J. Brown, Executive Vice President and Chief Preservation Officer for the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Brown says restoring areas like Jefferson Chalmers have a value beyond the historical. It’s just better economics.

“So for every dollar of federal tax money that that is spent with the [federal] historic tax credit, we’re seeing $1.25 come back in from taxes into local, state and federal coffers.”

Even well past its prime, the Vanity still attracted solid names. Pictured here at center, Benny Goodman prior to a show in 1982. (PHOTO: Virtual Motor City)

Because of its rich cultural history, the National Trust named Jefferson-Chalmers neighborhood a National Treasure in 2016. It was the first such designation in the state of Michigan.

Both Brown and Elling emphasize that, whatever benefits come from restoring a city’s historical buildings, they should first serve those who live in the community.

“We don’t want to see new investment come in, new shops open up, and none of the jobs going to local residents,” says Elling. “That builds resentment – it builds a narrative of gentrification, it feeds into the narrative of the two Detroit’s: downtown Detroit for for wealthy folks, and the rest of the city.”

Nikita Wesley, co-owner of Red Bag Boutique, says support from community partners Shelborne Development and Jefferson East helped her and her sisters open their store.

Almost three years ago, Nikita Wesley and her sisters opened Red Bag Boutique across the street from Vanity Ballroom. She says working with Jefferson East and their partners, Shelborne Development, made a difference.

“They helped us with a lot – I mean a lot,” says Wesley. “Even in getting a website to get online so we can be international.”

And as more businesses begin opening up around her, Wesley says she’s optimistic for the neighborhood’s future.

“The area here is just so nice. Its up and coming. I wouldn’t trade it – even for a place in the mall, It’s very nice here.”

David J. Brown says the momentum for restoring these neighborhoods must be a community effort.

“[What] I really admire is the spirit of the people who who are wanting to see their city come back, and are making that investment,” Brown says. “Day after day, and they’re looking at what Detroit was, and the buildings that were part of the past, and they’re saying ‘you know what, we can reuse these and make that a part of our future.’

Joshua Elling of Jefferson East is one of the community partners working to restore the Vanity Ballroom – and its neighborhood of Jefferson-Chalmers.

And as to the fate of the Vanity Ballroom? Jefferson East and their partners say it’s in the works.

“It’s a huge cultural touchstone,” Elling says. “The community really wanted to see the ballroom brought back as some sort of community performance space. We’ve got it secured right now, but we’re still in active fundraising to bring this building back.”

CGTN America

CGTN America