Stories in this series

In the first of a three-part series looking at key moments in history which have helped shape Cuba today, CGTN’s Michael Voss looks back at the U.S. intervention in Cuba’s independence war against Spain and the U.S. occupation which followed.

In June 1889, thousands of U.S. troops began landing on Cuban soil in what was a decisive turning point in Cuba’s War of Independence against Spain.

Many of the troops landed in a sheltered natural harbor called Guantanamo Bay. One hundred and twenty-eight years later, the Americans are still there and to this day Cuba wants it back.

Cuba is the largest island in the Caribbean, strategically covering the sea routes on the southern flank of the United States. With its vast sugar plantations, Cuba in the late 19th century was one of the wealthiest and most industrialized islands. There were some in Washington who were keen to get rid of the Spanish and annex the island.

Cubans had been fighting off and on for their independence for almost 30 years. There was growing public concern in the United States over Spain’s brutal tactics of suppression with newspapers headlines calling on the U.S. government to intervene.

It was the fate of the battleship the USS Maine which proved to be the turning point.

The Maine had sailed into Havana Bay in January 1898 on a visit aimed at protecting U.S. interests and personnel here in case the fighting got out of hand.

But on the night of February 15th the Maine mysteriously exploded, killing more than 260 of the sailors on board. It may have been an accident, but the U.S. blamed the Spanish.

Artists impression explosion of USS Maine in havana Bay. The pretext for the American-Spanish war. (COURTESY: U.S. National Archives)

“Remember the Maine” became a battle cry which in April 1898 lead President William McKinley to formally declare war on Spain.

Felix Alfonso is Vice Dean of the University of Havana’s History Department.

“It was very hard for Cuba in that moment to accept such a poisonous gift that was offered. It was like a poisoned apple offered on the table.” Alonso told me.

“Cubans believed in the good faith of the United States, many of them had studied in the U.S. and saw the country as a nation of progress, freedom and democracy. But it was neither, progress, nor freedom nor democracy that they brought to Cuba.” He added.

What the U.S. intervention did bring was a rapid end to the war, a conflict the Cubans had been waging for almost 30 years.

The U.S. troops included volunteers like the Rough Riders, led by Theodore Roosevelt who went on to become President of the United States.

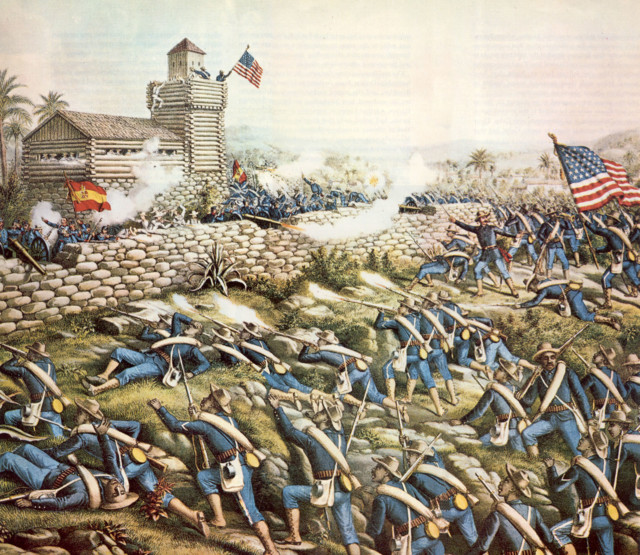

Roosevelt led his regiment in the decisive battle of San Juan Hill, a bloody head on assault against Spanish fortified positions on hilltops protecting Cuba’s second city Santiago.

This opened the way for American and Cuban troops to besiege Cuba’s second city. When the Spanish fleet tried to sail out of Santiago, they sailed into a trap with the U.S. navy sinking their entire Spanish fleet.

But when Spain surrendered, Cuba didn’t gain its independence. Instead it found itself under U.S. military occupation. Cuba didn’t even have a seat at the Treaty of Paris, where Spain not only ceded Cuba but also Puerto Rico along with the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific. For the first time the United States had become an imperial power.

The U.S. military occupation moved their headquarters into what had been the Spanish Governor’s palace in Havana, ‘El Palacio de los Capitanes Generales’.

The U.S. flag flew above the palace for the next four years.

In 1902, Washington finally handed Cuba its independence but with conditions, including leasing Guantanamo bay to the U.S. navy. The Platt Amendment also gave the U.S. the right to intervene in Cuban affairs to protect its interests.

For historian Felix Alfonso, the consequences of intervention and the Platt Amendment continue to have an impact on how Cuba sees its relationship with the United States.

“For 60 years, from January 1st, 1899 to January 1st, 1959 Cuba had to live its political life strongly subordinated to U.S. interests, firstly of a political nature and later of an economic nature.” He said.

The Cuban Revolution finally broke all links to the United States.

This fraught relationship appeared to finally be on the mend after Presidents Barack Obama and Raul Castro agreed, in December 2014, to restore diplomatic relations.

Even then the Cuban government made it clear that there could never be ‘normal’ relations with the United States, as long as Guantanamo Bay remains under U.S. control.

Now under U.S. President Donald Trump relations have deteriorated once again. Managing that relationship is one of the challenges Cuba’s next president will face.

CGTN America

CGTN America

San Juan Hill by Kurz and Allison. (COURTESY: U.S. National Archives)

San Juan Hill by Kurz and Allison. (COURTESY: U.S. National Archives)