At the Annual Prayer Breakfast on February 7, President Trump told a room full of religious leaders his administration would continue to support faith based adoption and foster care agencies who wish to use religion as a criterion for selecting – or denying – prospective parents.

President Donald Trump speaks during the National Prayer Breakfast, Thursday, Feb. 8, 2018, in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

“My administration,” Trump said, “is working to ensure that faith-based adoption agencies are able to help vulnerable children find their forever families while following their deeply held beliefs.”

Trump’s remarks come on the heels of a controversial January 23 decision by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). In that decision, Miracle Hill, a Christian foster care agency in South Carolina, was exempted from federal non-discrimination laws.

Because Miracle Hill receives federal funding, the decision is seen by many as government endorsement of both religion – and religious based discrimination. A clear conflict with the First Amendment.

The legal grounds for HHS’s exemption is based on a 1993 law, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), that was designed to reasonably protect religious institutions and individuals from laws contrary to their faith.

After more than 25 years, views on that law – and how it has been transformed – have fallen into opposite corners: those who believe it is essential to religious liberty under the First Amendment, and those who believe it creates a legal backdoor for unlawful discrimination.

Miracle Hill

In 2017, Beth Lesser signed up for a three-day foster care training program in Greenville, South Carolina. It was co-hosted by Miracle Hill Ministries – a Christian charity that receives about half its budget, almost $600,000 annually, from federal and state funding.

According to Lesser, on the third day of training, officials running the program told her only Protestant Christians would be allowed to participate in Miracle Hill’s foster program.

Beth Lesser is Jewish.

“I was the only Jewish person,” Lesser told Forward Magazine. “It was humiliating to be told essentially, Christians over here, Jews over there… What Miracle Hill is doing is not religious freedom,” she continued. “They are hiding behind that to discriminate, plain and simple.”

Under regulations set during the Obama administration, adoption and foster care agencies that receive federal funds are barred from discriminating on the basis of age, disability, sex, race, color, national origin, religion, gender identity, or sexual orientation.

South Carolina’s Department of Social Services (DSS) had received multiple complaints about Miracle Hill, including from same-sex couples who were also turned away. In 2018, DSS informed the Miracle Hill it was at risk of losing both state and federal funding – as well as its license to operate.

However, in support of Miracle Hill, South Carolina’s Republican Governor Henry McMaster issued an executive order allowing faith based organizations contracted by the state – and receiving state funds – the right to effectively discriminate based on their religious values.

On January 23, McMaster also acquired a waiver from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that exempted Miracle Hill from federal non-discrimination laws.

Within the waiver, HHS Assistant Director Steven Wagner stated that forcing a Christian ministry to accept applicants outside of their faith would “cause a burden to [their] religious beliefs that is unacceptable under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).”

Religious Liberty in U.S. Law

Amish children fleeing police and truancy officers in Hazelton, Iowa, 1965. (PHOTO: Des Moines Register)

Though there are many laws concerning religious liberty in the U.S., they are all rooted in the Constitution’s First Amendment’s Establishment and Free Exercise clauses. The relevant text reads:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”.

Over time, interpretation of the Free Exercise clause has been controversial – especially when clashing with other constitutional rights.

But in the early 1990s, after a controversial Supreme Court ruling on Native American religious rituals, Congress was moved to set a more concise legal framework for questions of religious liberty. The result was 1993’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

Before we get into the RFRA, let’s have a look at preceding legal cases cited in its foundation.

Adeil Sherbert, 1963

Sherbert v. Verner – 1963

Adeil Sherbert, a Seventh-day Adventist, was fired from a job of 35 years for refusing to work on Saturdays – her religion’s day of Sabbath. After being told by South Carolina her inability to work on Saturdays was a personal choice, she sued the state for denying unemployment benefits.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Sherbert’s favor, with Justice Brennan stating “to condition the availability of benefits upon this appellant’s willingness to violate a cardinal principle of her religious faith effectively penalizes the free exercise of her constitutional liberties.”

Amish children flee a local police officer into nearby cornfields. (PHOTO: Des Mones Register)

Wisconsin v. Yoder – 1972

After withdrawing their children from public education in favor of religious homeschooling, members of an Amish Mennonite community were convicted of violating Wisconsin’s truancy and child welfare laws.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Amish, stating that to force them to school their children outside the religious community was a violation of their First Amendment rights.

Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith – 1990

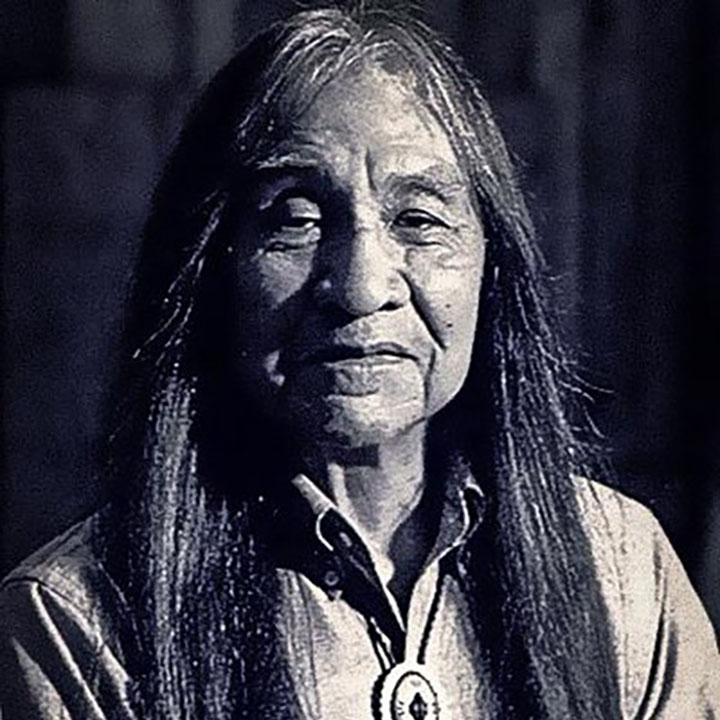

Native American Alfred Smith’s SCOTUS case led to the RFRA being passed.

Two Native Americans were fired from their jobs at a drug clinic in Oregon after it was learned they had consumed peyote, an illegal hallucinogen, as part of a religious ritual outside of work.

In addition to being dismissed, they were also denied unemployment benefits from the state.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Native Americans. Writing for the majority, Justice Antonin Scalia stated that granting religious exemption for illegal drug use “would open the prospect of constitutionally required exemptions from civic obligations of almost every conceivable kind.” He went on to cite military service, payment of taxes, vaccination, child-neglect, animal cruelty, and even traffic laws as examples.

Religious Freedom Restoration Act – 1993

President Bill Clinton signs the 1993 RFRA into law. (PHOTO: White House)

Backlash followed the high court’s ruling on Employment Division/State of Oregon v. Smith, with many saying the precedent threatened First Amendment protections for all Americans.

As a result, in March 1993, Congressman Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) introduced the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

In its language, the bill acknowledged that even laws “neutral” towards religion, still had potential to burden an individual’s right to religious exercise.

As its standard, the RFRA put forth what is known as the ‘Sherbert’ test, requiring government to demonstrate “compelling state interest” for any measure that could restrict religious practice. It also elevated the legal status for those wishing to be exempt from laws contrary to their faith.

The law had bipartisan support in congress, as well as a wide coalition of religious and civil rights groups. Among them, the National Association of Evangelicals, the Southern Baptist Convention, the American Jewish Congress, the Mormon Church and the American Civil Liberties Union.

The RFRA was passed almost unanimously by the U.S. Congress, and signed into law by President Bill Clinton later that year.

But little over twenty years later, another case before the Supreme Court became a rallying cry for civil rights activists who believed the RFRA had gone too far – in the wrong direction.

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., et Al – 2014

The SCOTUS ruling on Hobby Lobby raised alarm bells with those who feared religious liberty had gone too far. (PHOTO: AP)

After the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, employers were required to meet requirements in health insurance provided to employees. One of those requirements was contraceptive and birth control coverage for female workers.

Hobby Lobby, which at the time employed about 13,000 workers in the U.S., refused to provide that coverage because it conflicted with the conservative Christian views of its founder, David Green.

Being in violation of the ACA, the company faced penalties for each employee – potentially amounting up to $475 million dollars per year.

While churches and other religious institutions are exempt from the contraception mandate, privately owned businesses are not.

The question before the high court became: Can a for-profit corporation claim religious burden – above the rights of its employees under federal law?

In 2014, a closely divided (5-4) Supreme Court expanded the RFRA to allow Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood Specialties – a smaller, Mennonite owned company – to claim religious exemption from the ACA mandate.

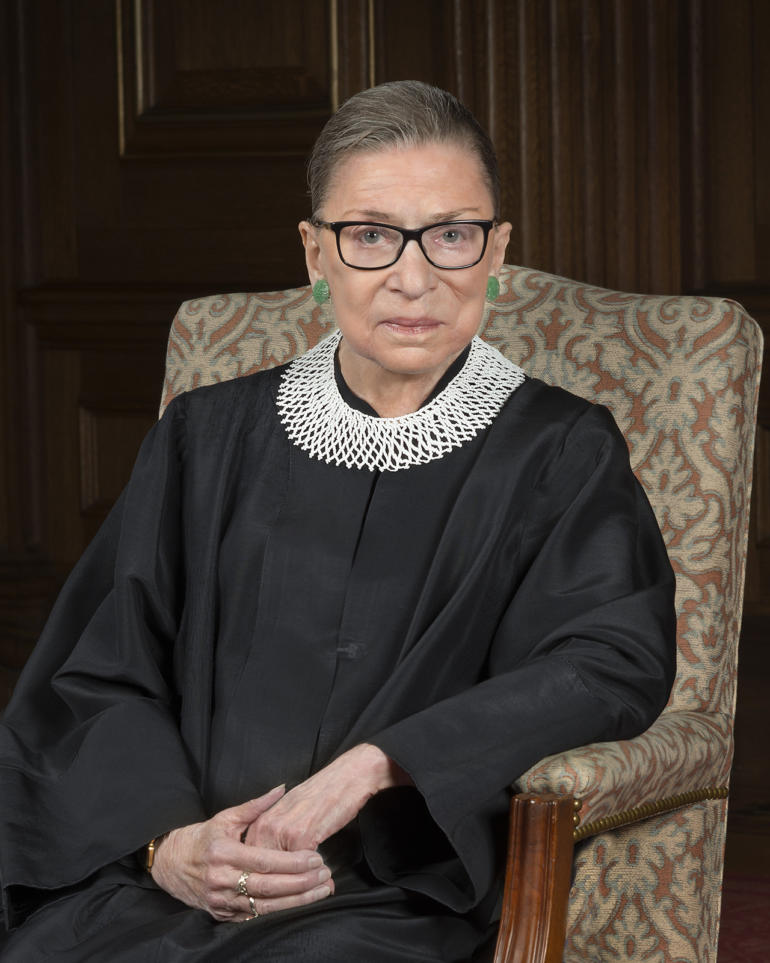

Ruth Bader Ginsburg. (PHOTO: U.S. Supreme Court)

In a sharply written dissent for the minority, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg articulated the view that exemptions under the RFRA should not apply to for-profit entities.

“The reason why is hardly obscure. Religious organizations exist to foster the interests of persons subscribing to the same religious faith. Not so of for-profit corporations. Workers who sustain the operations of those corporations commonly are not drawn from one religious community. Indeed, by law, no religion-based criterion can restrict the work force of for-profit corporations…

…In sum, with respect to free exercise claims no less than free speech claims, “‘[y]our right to swing your arms ends just where the other man’s nose begins.’ [Chafee, Freedom of Speech in War Time, 32 Harv. L. Rev. 932, 957 (1919)]”

For the majority, Justice Samuel Alito countered Ginsburg, stating religious exemption for Hobby Lobby was limited in scope. He also pointed out employees would still have reasonable access to contraception coverage outside of the company – including accommodations previously made under ACA for employees of religious institutions.

Religious conservatives applauded the Hobby Lobby ruling. Jessica Marshall, VP for The Heritage Foundation’s Institute for Family, Community & Opportunity wrote:

“The Constitution and RFRA supply effective tools for protecting religious liberty, even in a culture with deep disagreements on issues such as abortion. You don’t have to agree with the Hahn and Green families’ decision to support their freedom to make that decision.”

Still, Ginsburg predicted that, with the majority’s logic used for Hobby Lobby, there was “little doubt that RFRA claims will proliferate.”

Do No Harm? The Future for the RFRA

Unlike the bipartisan support for the original bill, views on the present and future of the RFRA fall, almost exclusively, on political and ideological lines.

“Unfortunately in recent years,” said Congressman Joe Kennedy III (D-MA) . “that legislation [RFRA] has been used as cover to erode civil rights protections, equal access to health care and child labor laws. In the face of mounting threats from an Administration that continues to back away from civil rights protections, the Do No Harm Act will restore the sacred balance between our right to religious freedom and our promise of equal protection under law.”

In 2017, Congressmen Joe Kennedy III (D-MA) and Bobby Scott (D-VA) introduced the Do No Harm Act, H.R. 3222, in the House of Representatives. An identical bill was introduced in the Senate, by Senator Kamala Harris (D-CA) in 2018.

The bill would “limit the use of RFRA in cases involving discrimination, child labor and abuse, wages and collective bargaining, access to health care, public accommodations, and social services provided through government contract.“

In this May 4, 2017 file photo, President Donald Trump holds up a signed executive order aimed at easing an IRS rule limiting political activity for churches in the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington. In an order that undercuts federal protections for LGBT people, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a sweeping directive to agencies Friday to do as much as possible to accommodate those who claim their religious freedoms are being violated. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

In contrast, since President Trump took office, his administration and Republican lawmakers have encouraged further expansion of RFRA’s protections and exemptions – even where it conflicts with other civil rights and non-discrimination laws.

In 2017, Trump issued an executive order, “Promoting Free Speech and Religious Liberty,” which was followed by then Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ Department of Justice guidance, “Federal Law Protections for Religious Liberty.” Both documents encourage governing agencies, like the HHS, to favor RFRA’s religious exemptions – even where it conflicts with other civil rights and non-discrimination laws.

“To the greatest extent practicable and permitted by law, religious observance and practice should be reasonably accommodated in all government activity, including employment, contracting, and programming” stated Sessions in his DOJ guidance document.

According a report by liberal think-tank Center for American Progress, and Columbia Law School, the DOJ guidelines “undermine” over 87 regulations, 16 agency guidance documents and 55 federal programs and services where non-discrimination laws are applicable.

While Republicans controlled Congress, both versions of the “Do No Harm Act” never made it past committee. However, after Democrats won the House in 2018, it is more likely these debate will make it to the floor.

Following HHS’s Miracle Hill decision, Rep. Kennedy told the National Journal he will soon reintroduce the “Do No Harm Act”.

However, with the queue of opposing legal actions continuing to grow across the federal government – and the states – a prediction for RFRA’s future in civil life is still elusive.

POSTSCRIPT: State versions of the RFRA

Demonstrators gather at Monument Circle to protest a controversial religious freedom bill recently signed by Governor Mike Pence, during a rally in Indianapolis March 28, 2015. More than 2,000 people gathered at the Indiana State Capital Saturday to protest Indiana’s newly signed Religious Freedom Restoration Act, saying it would promote discrimination against individuals based on sexual orientation. (PHOTO: REUTERS/Nate Chute)

Since its inception, 21 states have passed their own versions of the RFRA, which clarify or expand religious exemptions. Some have been more controversial than others.

Indiana

In March 2015, under then Governor Mike Pence, Indiana passed its own RFRA allowing business owners to deny services to LGBTQ on religious grounds.

Mississippi

In the 2016 Protecting Freedom of Conscience from Government Discrimination Act, Mississippi guarantees the state will not prosecute those who refuse to provide services based on religious opposition to same-sex marriage, extramarital sex or transgender people. Among other allowances, the law also protects state employees who refuse to license marriages, or those who refuse to provide medical services based on those oppositions.

South Dakota

South Dakota Gov. Dennis Daugaard and the state legislature passed a measure allowing tax-payer funded foster care or adoption agencies to deny services to same sex, or LGBTQ couples based on religious or moral objections. The law, however, does not require those agencies to be religiously affiliated.

CGTN America

CGTN America