In the final installment in our series examining the human side of illegal immigration in the United States, CGTN’s Alasdair Baverstock reports on the U.S.-born children of undocumented immigrants.

A Mexican family separated for 20 years – allowed to reunite, for a short time, as part of a U.S. migrant reunion program.

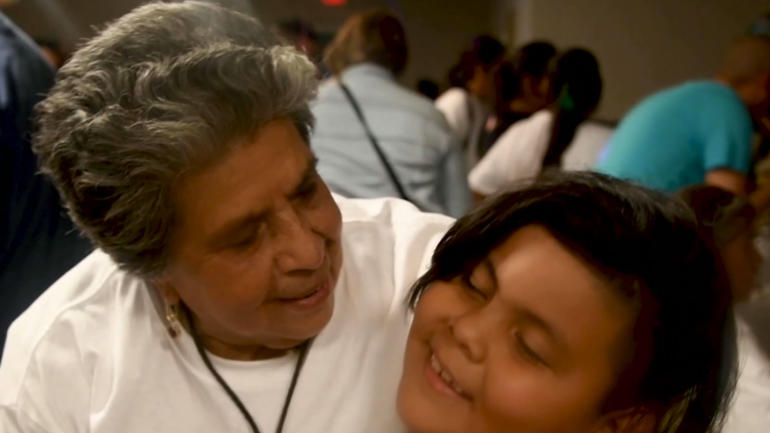

After two decades, a family reunion.

A mother from Mexico flies to the United States to see her daughter, an undocumented immigrant, and her American-born grandchildren she’s never met.

Each lives through illegal immigration in their own way.

At age 73, Imelda Gil is meeting her grandchildren for the first time, allowed to travel to the U.S. as part of a Mexican-U.S. cooperative program to reunite families separated by migration, if only for a visit.

Imelda’s daughter and son-in-law are undocumented, and while they came here in hopes of a better life, they live in constant fear of the authorities’ knock at the door.

But for father Victor, the hardest part is already over His children, born in the U.S., are legally Americans.

“For me, the difference for my children is that they won’t have to suffer like I did to get here. If they want to come, they just come. They don’t have to suffer and cross the deserts, or the mountains. That’s the only difference,” Paz said.

Yet the U.S.-born generation nevertheless feels the daily angst of undocumented life.

Diana Cuevas’s grandparents shared a plane with Imelda, part of the same migrant reunion program They, too, were meeting for the first time. Later, Diana described to us a constant fear and stress, knowing loved ones could be deported at any time.

“The pain of seeing that your family members are some of the ones to get deported, people you know, people you’ve grown up with, people you’ve seen have kids, grandkids even, and they get deported. The only thing you can do is be scared all the time,” Cuevas said.

For Diana, a dental assistant pursuing a degree in dentistry, the removal of her mother would also drastically change her own life.

“If my mom was to, for any reason, not be here with us, I know not only would it break all of our hearts, it’s like having half of you being gone away. Then not only would I have to be responsible for her over there, but also responsible for my brother and my sister here,” she said.

For the next generation, stuck between their family and their future, there’s often a pervasive feeling of insecurity, seen on a daily basis by immigration attorney Paola Ramirez.

“Of course their children feel that, because they don’t feel that they belong here, and they think that their parents could be taken away, or that their parents will take them to a country that they don’t even know,” Ramirez said.

For Victor, family unity is paramount.

“The only option is for us to be together, because in reality, you can’t do it any other way. Here you just live day-to-day, maybe one day you leave for work and you don’t come home. But this country has given us a lot, that’s why we’re here. For the moment, we’re still here,” Paz said.

For America’s undocumented immigrants, under new scrutiny amid the current administration’s enforcement crackdown – there are few alternatives to embracing that ‘day-to-day’ approach. Still, most hope for more.

CGTN America

CGTN America