Currently some 1.6 million people in the United States are behind bars. About 650,000 of them are released from state and federal prisons every year. But studies show, within three years of that release two-thirds of them are likely to be rearrested, with half of those returning to prison. Why does the U.S. have such a high level of recidivism? And what makes it so hard for former inmates to re-enter society? Some answers in this special report by CCTV’s Roza Kazan.

Leslie Brown is a busy woman these days, running a support center for women just out of prison. Over two decades ago, she was one of them.

“I was charged with the max, with murder,” Brown says.

Brown was granted clemency after serving seven years of a 20-year sentence for conspiring to commit murder of her abusive husband.

Six years later, she opened Leslie’s Place, in her home to women released from prison.

“I had no money when God gave me the vision to do this. And I just took the ladies for the first three years and nobody paid me anything,” she said. “I just wanted to help them so they wouldn’t have to go back to prison.”

And so she helps them with getting state IDs and birth certificates, clothes, toiletries, bus cards, and computer training. She said when she was in prison she saw too many women come back.

“They would tell me there is no resources for women. Most of them had drug cases and they would always end up back because they said they couldn’t find a job, they had no money, they had no housing, and those things would cause them go back and do the same thing and get incarcerated again. It was a revolving door”

Regina Givens was one of those women. By 49, she had spent more than a decade behind bars. She’s now on electronic monitoring, and could have stayed with daughter. But she chose to come here.

“It just pushes me more to do more what I need to do for myself. Every program I can get in I am in it, any program, any help I can get, I am going for it, because I can’t go back to prison,” she said.

Brown hoped Givens would be one of the nearly 90 percent of women enrolled at her center that never go back to prison.

But the reality is more than half of former inmates in the United States are re-incarcerated within three years after their release.

Walter Boyd is the Executive Director at St. Leonard’s Ministries, a re-entry program that provides free counseling, food, housing and classes. He believed the stigma of having a criminal record is the main reason why so many former prisoners fail to rejoin the mainstream.

“They are many employers who knowingly will not hire someone with a criminal record,” he said.

In fact, most employers in the United States include a criminal background question on their job applications, something staff here believes is a major barrier.

“You feel out that application, you get that box and if you check it: yes, I’ve been arrested, or incarcerated, the person doing the hiring for the job, as soon as he sees that check, he throws in the garbage,” Victor Gaskins, the Program Director, said.

This has even sprung the so-called, “Ban-the-Box” movement. A campaign aimed at persuading employers to refrain from asking job applicants about their criminal history. Despite what the name suggests, supporters say they want to keep the criminal inquiry but ask employers to move it to a later stage in the hiring process.

“There should be a rational relationship between what is it that you are asking a person to do and how does their past impact that work,” Boyd said.

Over 45 U.S. cities and counties and seven states have “banned the box” on government job applications. Major retailer Target joined in October. But some experts say that’s not enough.

Michael Sweig is a former lawyer. In 1997, he voluntarily gave up his law license, pleaded guilty to a financial felony, and served four years of probation. Sweig said the lack of education, not the lack of jobs, was fueling recidivism. Sweig is the Founder of the Citizens’ Institute School for People with Criminal Records.

“On any given day in the U.S. there are four million people on probation and one million on parole. So five million people not incarcerated,” Sweig said. “Seventy to 80 percent of all those people are legally learning-disabled, [meaning] that they read 2-3 levels below their age or grade.”

This is why he wrote a bill to the Illinois state House and Senate on incentivized education for a system that would require as a condition of probation that all criminal defendants continue their education in exchange for time credits.

“If you’ve got a certificate, a degree, a diploma, you bring that to your probation office and that automatically reduces your probation sentence,” he said.

For instructors at St. Leonard’s, the focus is on the basics: how to build up self-esteem and teach former inmates to find jobs in an Internet-driven world.

“When they take our class, they learn how to make an online job application, work with email. Upload their resumes,” said Lynne Cunningham, Director of the Michael Barlow Center at St. Leonard’s Ministries.

It’s a complex problem, and a challenge officials at this Illinois prison say they strive to address even before the inmates get out.

Sheridan Correctional Center calls itself a therapeutic community, one of only two Illinois prisons dedicated to helping prisoners with addiction.

Three hours a day inmates spend in cognitive behavior therapy treatment, which officials believe will help them make better choices once out in the community.

“Abuse and addiction have to be addressed by the way that you think and the decision and the choices that you make on a day to day basis,” said Marcus Hardy, the warden at Sheridan Correctional Center.

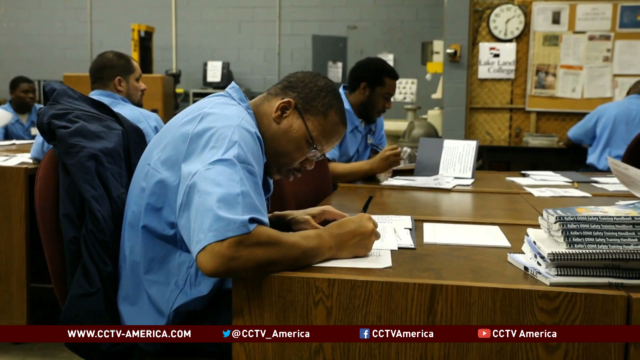

Another three hours a day inmates spend in class, learning shipping and warehousing or welding.

To serve their sentence here, they must apply and the smallest deviation in discipline will get them transferred back. For many, serving here has become a life-altering choice.

“If I was at another facility, I wouldn’t have been thinking positively, to better myself,” said inmate Michael McNeil. “I would have been doing the regular stuff that everyone else does, which is wake up, eat, work out and go back to sleep.”

“I might have been dead the road I was going in,” said inmate Cerriado Walton.

The cost of housing an inmate at the Sheridan Correctional Facility is nearly $28,000 a year. That’s 30 percent higher than the average cost at a correctional facility in the state of Illinois, but prison officials said the higher cost is worth the investment.

One number, they said, spoke for itself: the department’s recidivism rate is roughly 48 percent. At Sheridan, it’s about 20 percent lower than that.

Warden Hardy said classes and hands on experience will allow inmates to work in fields with no licensing requirements, or to start their own businesses.

“Our goal is to take an offender and turn him not into a tax consumer but into a tax payer,” he said. “So the question is, where is your dollar better spent?”

John Prince is a former Sheridan inmate. With three prison sentences behind him, he’s now working on his associate degree at St. Leonard’s.

“You are out of prison but you still need some help,” Price said. “You are on your own basically with just $20 and a train ticket, so where do you go from there? It’s the skills you need and reintegration programs [that help].”

And that, experts say, could be just one of the pieces needed to break the cycle of revolving-door incarceration in the U.S., one of the highest in the world.

Links: http://www.justice.gov/archive/fbci/progmenu_reentry.html

Leslie’s Place: http://www.lesliesplace.org/about.html

CGTN America

CGTN America