“Being a journalist in South Sudan is risking one’s life,” said John Gatluak, the editor at a community radio station there. “But I have dedicated myself to serving my community through radio as a watchdog, informing them about what the politicians are doing once the citizens elect them to power.” As a journalist in South Sudan, Gatluak faces no shortage of challenges. Months of violence in the country has only made a dire humanitarian crisis worse.

Follow John Gatluak on Twitter @12Manguet

On Tuesday, authorities in South Sudan shut down a popular radio station in the capital, Juba. Government security agents raided the Bakhita Radio station and arrested four employees. The news editor currently remains in detention. Presidential spokesman Ateny Wek said the station was a threat to national security by falsely reporting a rebel allegation that government forces had instigated the most recent fighting.

After several weeks of little to no violence, fighting broke out again in South Sudan last Friday. The country’s rebel leader and former vice president Riek Machar blamed the South Sudanese government for spending oil money on new weapons from the Chinese government amid mass hunger in the country. But U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry accused Machar of breaking the two peace deals that have been signed this year. Machar denied that his side is responsible for the violence and instead blamed South Sudan’s president, Salva Kiir.

MORE SOUTH SUDAN COVERAGE ON CCTV AMERICA.

The already ethnically-divided country has seen violent clashes from militias hunting members of specific tribes. At least six aid workers from the Nuer ethnic group were killed last Tuesday during an outbreak of militia violence. It is unknown exactly how many total have died in the conflict there overall, but reports in January showed more than 10,000.

Despite the most recent round of peace talks that began last week in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, no progress has been made toward ending the conflict. People living in rural and remote areas of South Sudan continue to face rising threats of violence and famine. The country is one of the U.N.’s largest aid operations, but it is chronically underfunded — the U.N. has only reached half of this year’s South Sudan appeal total. The need for more aid is still apparent because of the protracted period of violence and starvation.

The humanitarian crisis in South Sudan has caused at least one million people to become internally displaced, more than any other country in the world. Another 500,000 people have fled, and nearly four million of the country’s 11.3 million people (about half the size of Texas) are at risk of starvation. A top U.N. official said last week that the three-year-old country is “on the brink of a humanitarian catastrophe.”

Besides the U.N., another group is trying to provide vital help for the people of South Sudan. Not in the traditional ways of giving food, money or medical supplies. Rather, they provide information that can be life-saving.

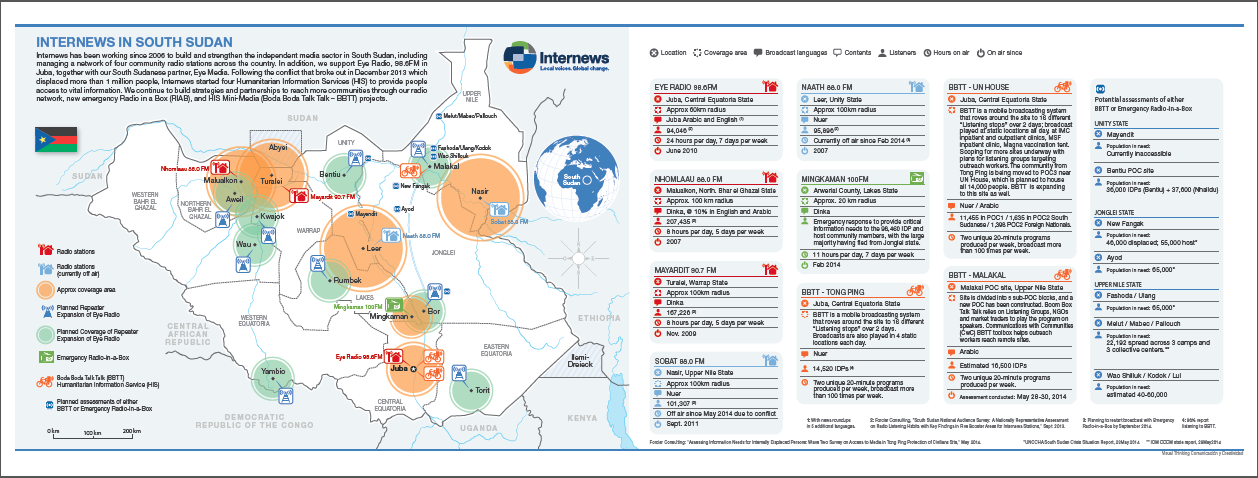

They are journalists like Gatluak who work with the non-profit organization Internews, a USAID-funded group which works to provide conflict-ridden and underdeveloped communities with resources to create reliable media networks. Founded in 1982 in northern California, Internews has worked in more than 90 countries across all continents. Their work includes providing funds to build radio stations and training journalists on conflict-sensitive reporting, among other efforts.. Most of their work is done by providing funds to build radio stations and training journalists on conflict-sensitive reporting, among other efforts.

Because of these media networks, Internews journalists have been able to save lives of South Sudanese people in remote areas who need accurate information — including whether current violence means it is safe to leave their homes or not.

In a recent report by the organization, an Internews-sponsored audio program called “Boda Boda Talk Talk” in internal refugee camps helped inform listeners on the current conflict in their country. The news was also useful in increasing health awareness and women’s rights. According to Gatluak, Internews is regarded as a reliable source by local citizens. He feels that the community needs such services.

John Gatluak, managing editor at Internews Community Radio Network. Photo courtesy of Jean Luc Dushime/Internews.

“I find that my community is not well informed about their rights in the South Sudan interim constitution,” Gatlauk told CCTV America. “If I don’t give them the information, who else would do it?”

Journalists in conflict zones like South Sudan face an increased amount of risks. Gatluak was forced to flee the town of a previous radio station when South Sudan government forces arrived. He was in hiding in the wilderness of the Nile wetlands for nearly two months before he was able to reach refuge in Juba.

The South Sudan government views journalists negatively out of fear that the media will expose things to the citizens that would make them even less popular amidst the ongoing crisis, according to Gatluak. After the raiding of the Bakhita Radio station in Juba, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ East Africa representative Tom Rhodes said the government “has repeatedly taken a heavy hand to the media, even as political instability underlines the public’s need for independent sources of information.”

“Journalists are being intimidated, detained, harassed, threatened and some lose their lives,” Gatluak said. “These are just a few of the challenges I face, and the list is endless.”

Report compiled with information from The Associated Press.

CGTN America

CGTN America