The stores in Washington D.C.’s Chinatown may bear Chinese names — along with their more-popularly known English names — but the downtown neighborhood is actually becoming far less Chinese due to increased development and high rents.

Watch CCTV America’s documentary “Chinatown Lost”

Over the last few decades, national and global chains have replaced mom and pop groceries, restaurants, and shops, as increased rents have forced many residents and businesses to the suburbs.

“The pressure is the tax of the real estate,” said Alfred Liu, the architect who designed the Chinatown Friendship Archway at the corner of 7th and H Streets NW that was erected in 1986. “Many Chinese find it hard to survive because of that. The taxes are too high and many Chinese restaurant can’t afford it.”

Liu hopes the Chinatown can still have an authentic Chinese feel.

Chinatown gate then and now.

“A city should not be uniform, it needs the colors of various ethnic cultures, and that’s what makes a city interesting,” Liu said. “If all elements of a city fall into the same pattern, it will be a city with no characteristics.”

Chinese immigrants first started settling in Washington D.C. in the 1880s along Pennsylvania Avenue and 4 1/2 and 7th Streets. The early immigrants were mainly men who had left wives to make fortunes in the United States with hopes to return. The first Chinese grocery store opened in 1892, according to the National Park Service. By 1903, the neighborhood was bustling with shops, laundries, tailor shops, restaurants and community organizations.

In the late 1920s, due to city redevelopment, Chinatown residents were displaced to the area near where it’s currently located downtown. By 1936, 800 people – including 32 families – were living in Chinatown, according to the NPS. They established Chinese schools, family associations, clubs, merchant associations, and entertainment facilities.

Photos and clippings of D.C.’s Chinatown over the years:

[flagallery gid=178](view full screen)

The neighborhood was hit hard in the 1968 riots that led to a decline in the downtown area, and many residents moved away. In the 1980s, the city built a new convention center that displaced Chinese residents once more. To provide housing for the displaced residents, Chinese community groups worked together to build the Wah Luck House apartment building at the corner of 6th and H Streets NW, designed by architect Liu.

In 1997 the neighborhood changed even more when the now-named Verizon Center was built. Since then high real estate costs and gentrification have priced out many Chinese, according to the Chinatown Community Cultural Center .

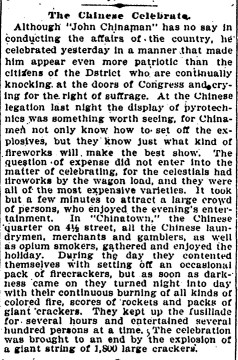

July 5, 1894 article in the Washington Evening Star references a Chinatown in Washington D.C. near 4 1/2 Street.

“Gentrification has produced a strange phenomenon in DC’s Chinatown. Local laws dictate that new businesses in the Chinatown area must have signs in English and Chinese, to preserve local character,” the cultural center writes on its website.

“Ironically most of the new businesses are national chain restaurants and stores, so that Starbucks, Hooters, and Legal Sea Foods, among others, hang their names in Chinese outside their stores.”

Over the past two decades, the Chinese population has shrunk from over 3,000 to about 300, the Washington Post reported.

Many Chinese-Americans, especially the second generation, have moved to Virginia and Maryland suburbs in Rockville.

Community leader Raymond Wong says that it’s a shame that it’s only the commercial aspect of Chinatown that’s visible to the public.

“The only part of culture you will see is [what] sells products,” Wong said. “The only thing you get now is kung pao chicken, spring rolls, and gift shops.”

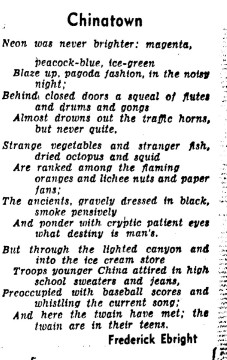

June 29, 1951 letter to the editor in the Evening Star features a poem about Chinatown in Washington D.C.

Wong, who runs the Wong People Kungfu Association tries to show the other side of Chinese culture by offering free martial arts classes to the public.

David Do, Director of Washington D.C. Mayor’s Office on Asian and Pacific Islander Affairs, said that for Chinese businesses to survive, they need better practices.

“That might mean working with them to change business practices so they can have longevity here in Chinatown,” Do said.

Jiating Xu, a Chinatown resident of 15 years, said she’s very concerned about how Chinatown has changed in the last few years. She misses the groceries, clinics, and restaurants that made living in the neighborhood comfortable and convenient. Now, she and many of her neighbors must catch a carpool a half-hour away to Virginia to buy Chinese groceries.

“I just wish Chinatown could have a Chinese clinic, and we old people can go there with no communication barriers,” Xu said.

“The United States is a multicultural country, a multicultural society, and we are all part of it. So shouldn’t we all be protected?”

Text story by Siqi Lin.

Vincia Lan on promoting Chinatowns in the US

CCTV America’s Mike Walter spoke to Vincia Lan, who works every day to promote Chinatowns in the United States as well as Chinese-owned businesses.

CGTN America

CGTN America