The delegations of 175 countries gathered at the U.N. headquarters in New York City Friday, Earth Day, to sign the Paris Agreement on climate change. Here’s a quick primer on what it is, who’s signing, and why it’s important.

What is it?

An international agreement to bring down pollution levels (carbon emissions), which in turn would slow global warming and prevent disastrous environmental outcomes. It’s name comes from the city where the negotiations took place.

The agreement’s goal is to keep “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels.”

The 1.5 degrees Celsius level was pushed hard by small, low-lying island nations, which are particularly at risk from being swallowed up by the ocean due to rising sea levels. (However, experts believe that level is too aggressive based on current projections, and highly unlikely to be met.)

Why is it needed?

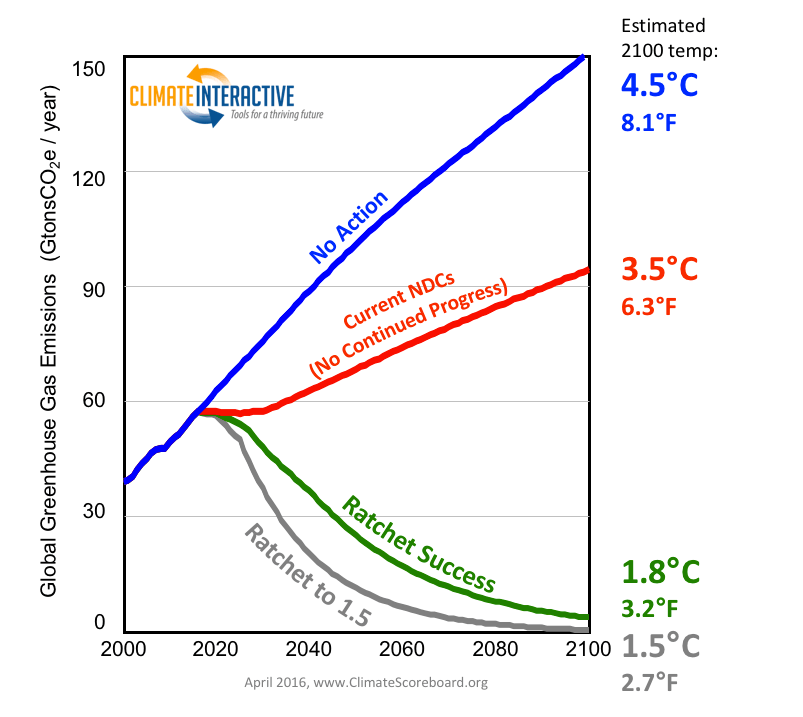

Some scientists estimate that if nothing is done to curb greenhouse gas emissions, the planet could warm by 4.5 degrees Celsius (8.1 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2100. This chart by Climate Interactive shows estimates for warming based on different levels of action.

Scientists studying the impact of increased global warming found that even a 0.5 degree Celsius increase from 1.5 to 2 degrees of global warming “would lead to longer heatwaves, greater droughts and, in the tropics, reduced crop yield and all coral reefs being put in grave danger,” according to The Guardian.

What is the the world’s current environmental status?

A century-long record was broken in March — and by the largest margin — according to the Japan Meteorological Agency. Global temperatures reached 1.07 degrees Celsius hotter than the 20th century average, marking the warmest since the agency began tracking the data in 1891.

The U.N.’s World Meteorological Organization said March’s heat “smashed” records.

JMA: Global temp records smashed (again) in March, 1.07°C above 20th C avg https://t.co/erhOM82T0X #climateaction pic.twitter.com/uR0GpMTd6Q

— World Meteorological Organization (@WMO) April 14, 2016

NASA recorded a slightly higher March figure — 1.28 degrees Celsius above the 1951-1980 average.

Those increases, scientists say, lead or contribute to weather and climate events that can have extraordinarily negative consequences. Island nations could slip into the increasingly-rising seas; ice sheets in Antarctica could melt and expose long-encased soil to the air and decomposition, which in turn would release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Marine life, plants and animals also may not be able to adjust quickly enough to a changing ecosystem.

In 2016 alone, the world has seen “the strongest hurricane on record for both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, unprecedented continuing drought in California, the warmest start to a year that we’ve ever seen, on the heels of what was the warmest full year on record for the globe,” Michael Mann, a climate researcher at Pennsylvania State University, told The Washington Post.

Who is signing the agreement?

For the Paris Agreement to take legal effect, 55 countries representing 55 percent of global emissions must formally sign on.

The world’s largest polluters, China and the U.S., together make up about 44 percent of all CO2 emissions. (The 28-country bloc of the EU is third, followed by India, Russia, and Japan.)

In December 2015, 197 nations adopted the agreement. To officially join, countries must sign and then submit an “instrument of ratification, acceptance or approval.”

The U.S. and China, along with 173 other countries, signed the agreement Friday.

How will the agreement be carried out?

Countries and territories pledge they will “reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible.” While a target date isn’t specified, the agreement spells out that rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions should be made “in accordance with best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century.”

Each country will have a national climate action plan and targets for reduced emissions levels (called “Nationally Determined Contribution” or NDC).

“The NDCs underpin the world’s ability to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement—including limiting temperature rise to 1.5-2 degrees C—and prevent the worst impacts of climate change,” the World Resources Institute said in a post.

China pledged that its CO2 emissions will level off or decline by or around 2030, and the government said it plans to source 20 percent of the country’s energy from non-fossil fuels.

A consistent voice for China’s forefront role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, President Xi Jinping has stressed his commitment to curbing global warming.

During Xi’s state visit in September, China matched the U.S. contribution of nearly $3 billion to help developing countries combat climate change. And perhaps its greatest impact, aside from reducing its own carbon footprint, will be to inspire other major economies to pledge ambitious reduction targets.

The U.S. had pledged to cut emissions to at least 28 percent from 2005 levels by 2025, but that was shelved by the Supreme Court until legal challenges are resolved on a major coal-fired power plant greenhouse gas regulation that the administration considered instrumental in reaching that target.

CGTN America

CGTN America