Since it’s early inception in 2006 — when the Islamic State was an offshoot of al-Qaida in Iraq — through its later evolution into ISIL, the terror organization has been the target of the international community.

The international campaign against the group has taken its toll on ISIL’s financing, but in large part, has not completely crippled them.

ISIL’s formation as a self-proclaimed “caliphate” meant that the group governed over the land it seized, without having the financial and institutional obligations of a traditional government. They have also based their financial gains on exploiting the resources of the land they control.

“Its territorial holdings thus provide ISIS with a self-sustaining and diversified economic system,” said a report by the French-based Center for the Analysis of Terrorism.

“Its ability to secure its internal resources without dependence upon external funds explains the group’s financial power and amounts to an unprecedented political challenge with regard to combating the financing of terrorism.”

ISIL is “very used to folding back and going into terrorist mode and that is a much lower cost,” said Howard Shatz, a Senior Economist with the RAND Corporation.

The terror organization does “some things cheaply, but not as cheaply as people think—they pay salaries and those salaries are based on family size,” Shatz said. “[But] they are not a normal government and they don’t have to spend on social services… they don’t have to, and they don’t.”

Despite this, years of unrelenting airstrikes by a U.S.-led coalition, as well as Russia, has affected ISIL.

Estimates by one research center show that in 2015, ISIL had oil revenue of about $600 million, compared with more than a billion dollars a year earlier.

But oil is not the only source of its revenue.

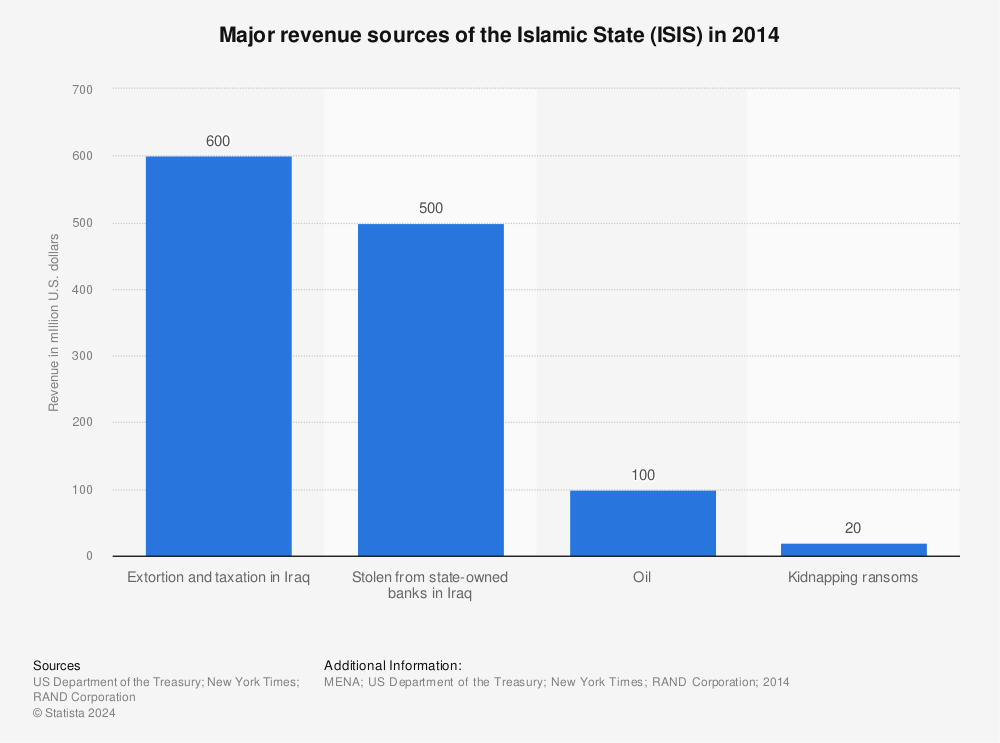

A 2015 New York Times report based on RAND numbers shows that oil only makes up a fraction of its revenue.

Find more statistics at Statista

In 2014, ISIL’s major revenue came from extortion and taxation in Iraq (around $600 million), money stolen from state-owned banks in Iraq (around $500 million), oil (around $100 million) and ransom from kidnappings (around $20 million).

“At this point, their real power of raising revenue comes from their territorial control,” Shatz said.

“They have a population under their control—they tax that population, they have resources under their control, not just oil, and they have agricultural land, they have factories, and they can tax that agricultural land, they can sell the production from factories and take a small portion of illicitly exported antiquities, though that’s not a large part of their money, but it does add up.”

Shatz said the terror group is not doing well financially under years of an airstrike campaign that started in 2014.

“I do not think they are financially healthy, because their revenues have gone down and one other component of the bombing campaign was attacks on their cash storage sites… so if we destroy cash holdings, it’s not like they can revert to charging things,” Shatz said.

“As far as how their financing affects their ability to carry out terror strikes, the RAND expert said “we do know that there’s a correlation between their spending and the pace of their attacks.”

CGTN America

CGTN America