In a small coastal classroom in Yonabaru, southern Okinawa, teenagers are learning to speak words in a language that is slowly dying off.

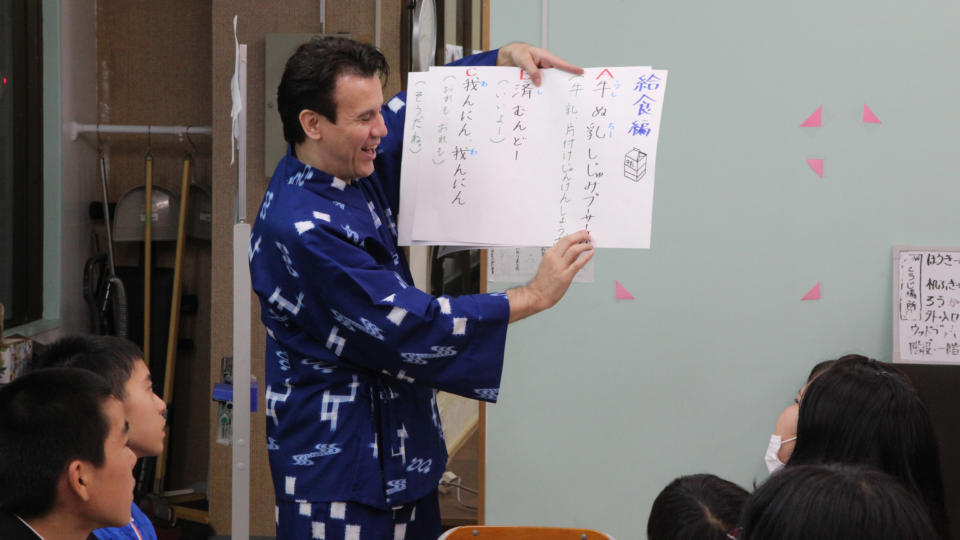

“Chibariigo!” urges their teacher Byron Fija, which means “go for it” in Uchinaaguchi, the main Okinawan language.

Fija claps his hands, encouraging his students to speak loudly and confidently as they introduce themselves in Uchinaaguchi.

The students are hesitant. They’ve only taken a few Okinawan classes as part of their “cram school” (a private supplementary classes) curriculum, and even that is more Okinawan than most Japanese students will ever experience.

The only reason Uchinaaguchi is even part of their curriculm at all is because the owner of cram school, Coral House Juku J&S, believes in the importance of retaining cultural heritage, Fija said.

Byron Fija plays the sanshin, an Okinawan instrument as he sings an Okinawan song. (Photo: Tianyu Wang)

It’s a sentiment that’s growing.

In 2015, UNESCO added Okinawan to the list of endangered languages in the world with only 400,000 speakers in 2014.

Of Japan’s eight endangered languages, six are in the Ryukyu Islands – a chain of islands the largest of which is Okinawa.

Most speakers are elderly.

A recent poll by Okinawan newspaper Ryukyu Shimpo found that in January 2017, while 41.2 percent of Okinawans can speak Okinawan languages, but only 7.5 percent of Okinawans in their 20s could speak it.

The history of the decline of Okinawan langauges is due in large part to the Japanese government, Fija said.

When Japan took over the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1879, speaking native languages became discouraged and all schools were required to teach only Japanese. Students caught speaking native languages were often forced to wear a plaque around their neck called “dialect card” as a form of punishment.

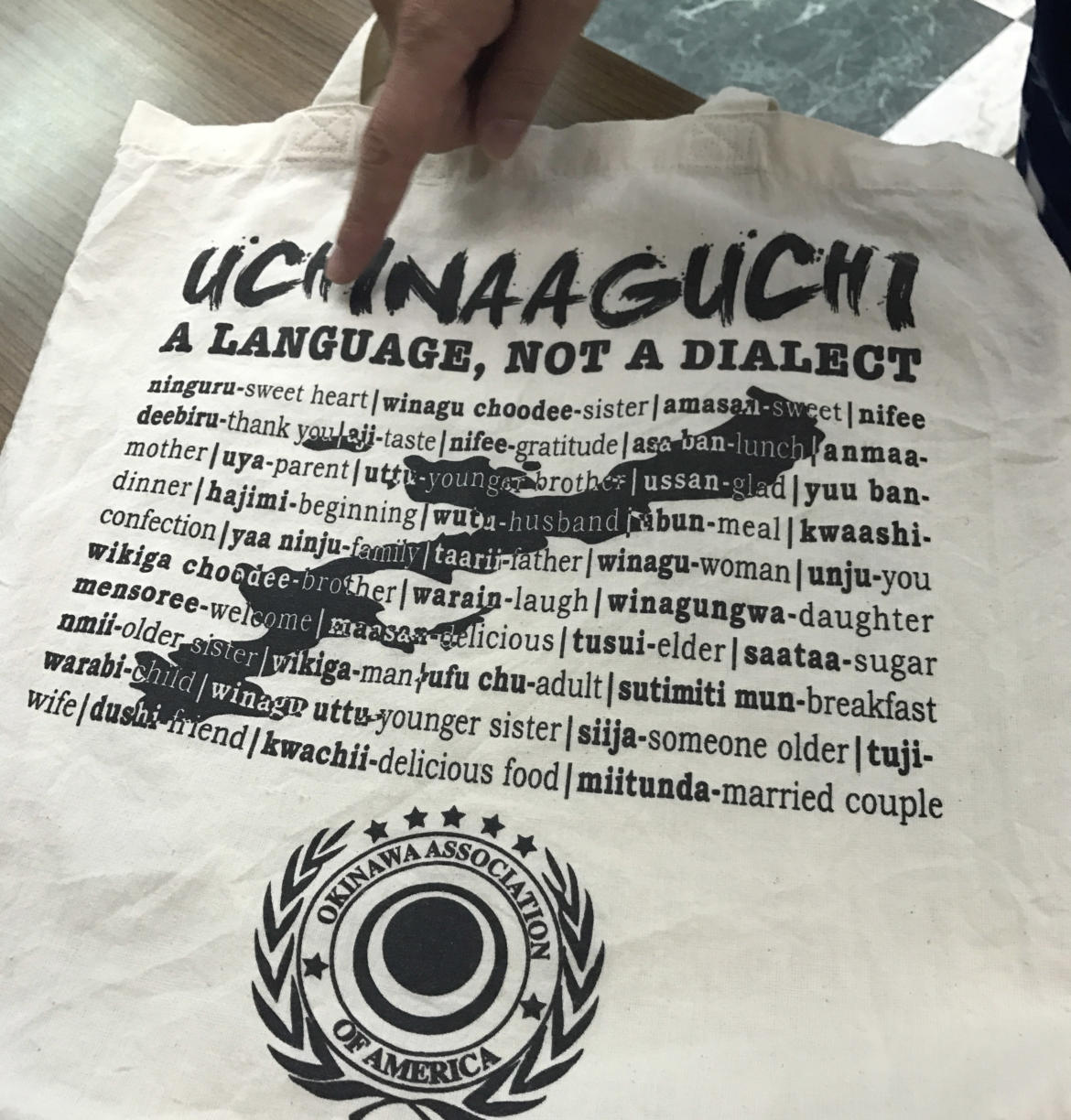

Scholars argue that contrary to the popular and historically-forced view, Okinawan is not a dialect of Japanese but a different language.

Only about 60 percent of Uchinaaguchi and Japanese words are the same, Fija said, which is less than the similiarities between English and German words.

“Okinawans were forced to make their language as a dialect by the Japanese government,” added Shinsho Miyara, an professor emeritus of linguistics at the University of the Ryukyus and the chairman of the Ryukyu Heritage Language Society.

Okinawan is also only a spoken language and many of pronunciations don’t exist in Japanese, making it harder to codefy in text, Miyara added.

Additionally, there are six separate languages in the Okinawan Islands, and while four of them in the northeast are similar, the rest in the southwest are very different, Miyara said.

A bag that expresses pride in the Uchinaaguchi language. (Photo: Tianyu Wang)

“I can speak a little bit Yaeyama,” Miyara said, “And it is entirely different from Uchinaaguchi.”

Yaeyama is both a language and the name of the town where Miyara was born in Ishigaki Island, which is closer in proximity to Taiwan than to Okinawa.

Professor Patrick Heinrich, who specializes in endangered languages at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice said the failure to maintain Okinawan languages is due to its lack of utility.

“People learn English because English does something for them,” Heinrich said. “For example, people can use English all over the world, or people can study abroad if they know the English. Uchinaaguchi has been detached from the utility.”

One way to maintain the languages is for the government to find a way to let people benefit from knowing it, Heinrich said.

“The best way for Okinawan government to revitalize Uchinaaguchi is requiring a language test on public servant recruitment,” Heinrich said.

“People who apply for the public servant job should at least pass the beginning level of the Uchinaaguchi test.”

Thanks to efforts by Miyara’s Ryukyu Heritage Language Society, the government has announced it would establish a center for the revitalization of the Okinawan languages, Miyara said.

But Miyara added that more can still be done.

“They should set the textbooks, standardize the writing system, and figure out the correct curriculums of Uchinaaguchi,” Miyara said.

“We, Okinawans, should push to add Uchinaaguchi to our elementary schools. This is our language. Our culture is based on the language.”

CGTN America

CGTN America