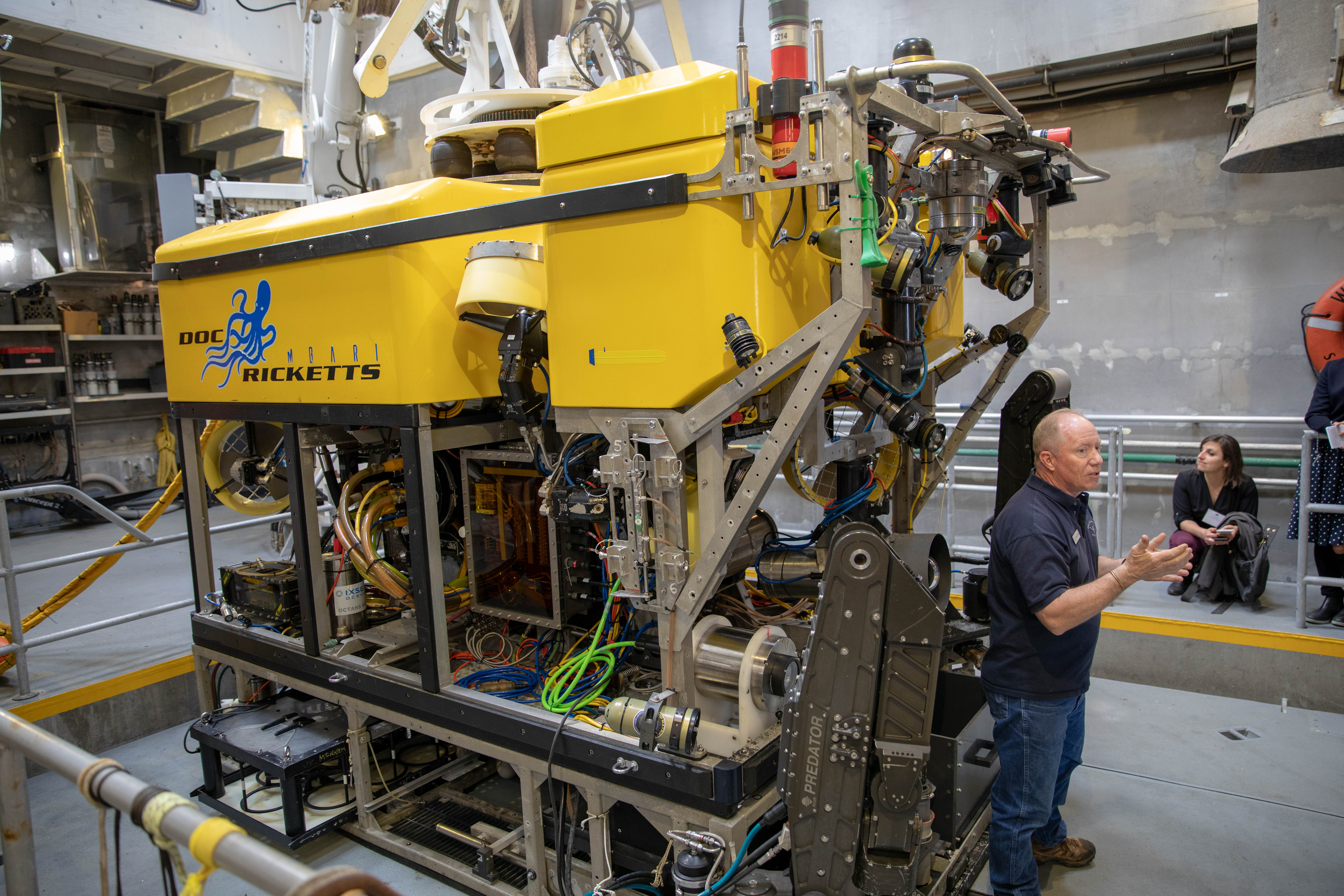

As a TV reporter, I thought I had a pretty cool job, but Pilot Knute Brekke has me beat – by several nautical miles. His office lies about 4,000 meters underwater, deep in the Pacific Ocean.

While I contend with daily snags on public transportation, Brekke commutes to work by navigating a remotely-operated vehicle or ROV, equipped with 15 cameras and robotic arms able to mimic seven functions of a human arm.

His goal: To try to document the myriad of species living in our oceans.

Brekke is by no means a one-man band: He works alongside dozens of scientists and engineers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in Moss Landing, California.

Monterey Bay is one of the largest marine sanctuaries and among the most protected areas in the United States. It’s known as the “Serengeti of the Sea,” encompassing more than 15,000 square kilometers of water and plunging more than 3,000 meters, which is twice the depth of the Grand Canyon.

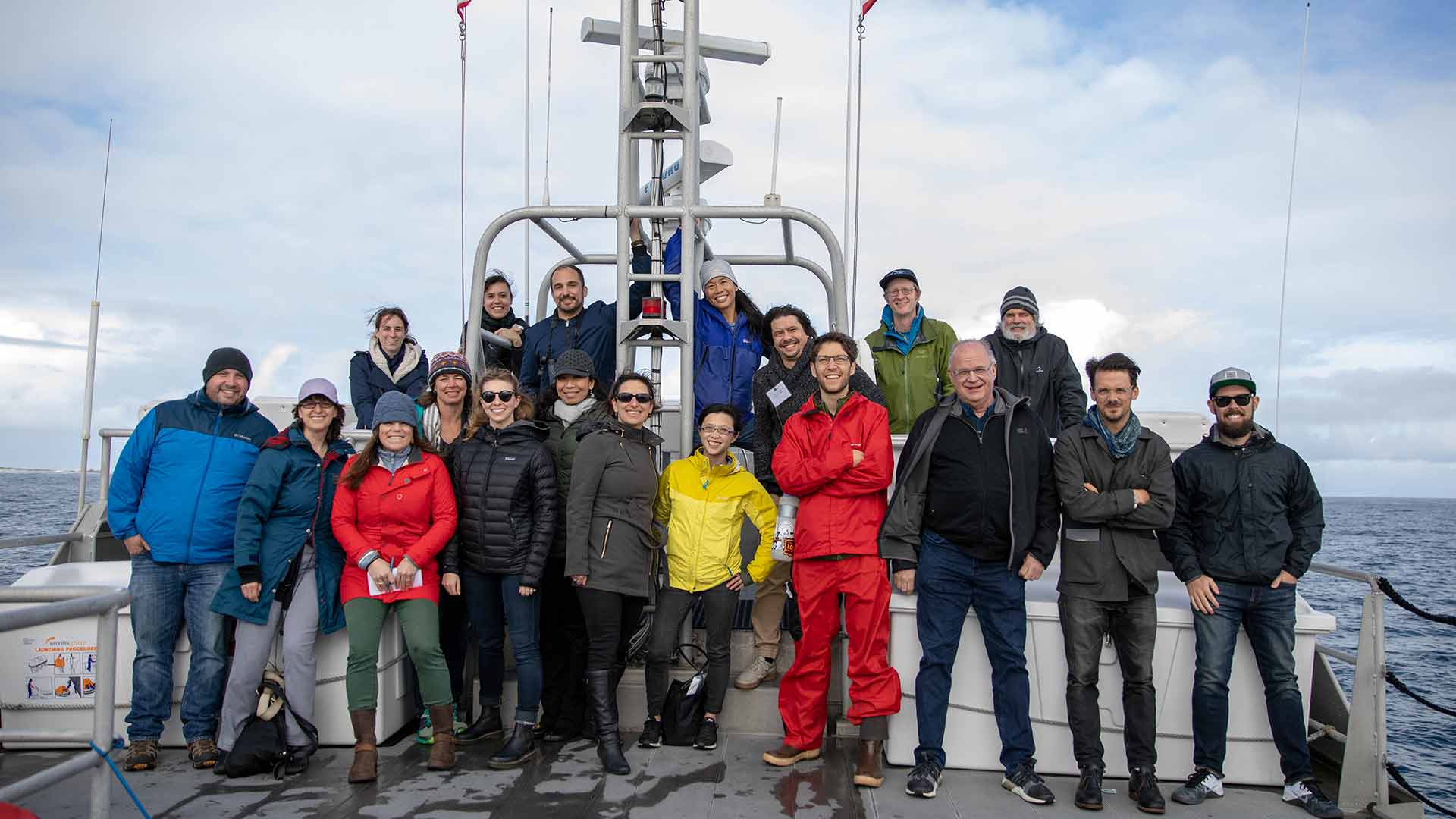

Journalists on boat tour on Monterey Bay. (Photo by the National Press Foundation)

It’s a marine biologist’s dream: the Bay teems with a diverse array of marine animals, including at least 525 species of fishes.

I recently had the opportunity to visit the Institute and other venues, alongside 19 other U.S.-based journalists, as part of a fellowship organized by the National Press Foundation. Over a jam-packed four days in Monterey and San Francisco, we talked with dozens of experts passionately dedicated to protecting our oceans and the communities living within them.

Ian Cole and Charlie Lambert talk to journalists. (Photo by the National Press Foundation)

At least half of the oxygen we breathe comes from plants in our oceans and we use the oceans for recreation, shoreline protection, transportation and food. It’s estimated 3 billion people around the world rely on wild-caught and farmed seafood as their main source of protein.

As global fish consumption grows, questions linger about how we can sustain the fish population for years to come. Fishermen we spoke with were frustrated with one stunning statistic we heard consistently throughout the fellowship: 90% of seafood in the U.S. is imported.

Ironically, that includes Monterey Bay, the same place brimming with various fish species. We discussed this with two local fishermen, Ian Cole and Charlie Lambert. Their frustration was evident when they talked about how fish were often taken out of the Bay, then sent immediately overseas for processing because of the cheap labor there.

“We get irritated when fish get on airplanes,” Lambert said.

The two took charge, developing Ocean2Table, a community-supported fishery. The duo works with commercial fishing vessels that help to market the seafood directly to consumers so customers have access to fish from the nearby waters that were caught that day, not months before.

Cataloging the Deep Blue

Who are our neighbors in the vast ocean? MBARI has a better idea than most. Four or five people make up MBARI’s Video Lab, which compiles one of the world’s largest databases of ocean life. They’re like librarians, but instead of books they spend half their work days annotating hours of underwater video footage like the kind that Brekke collects.

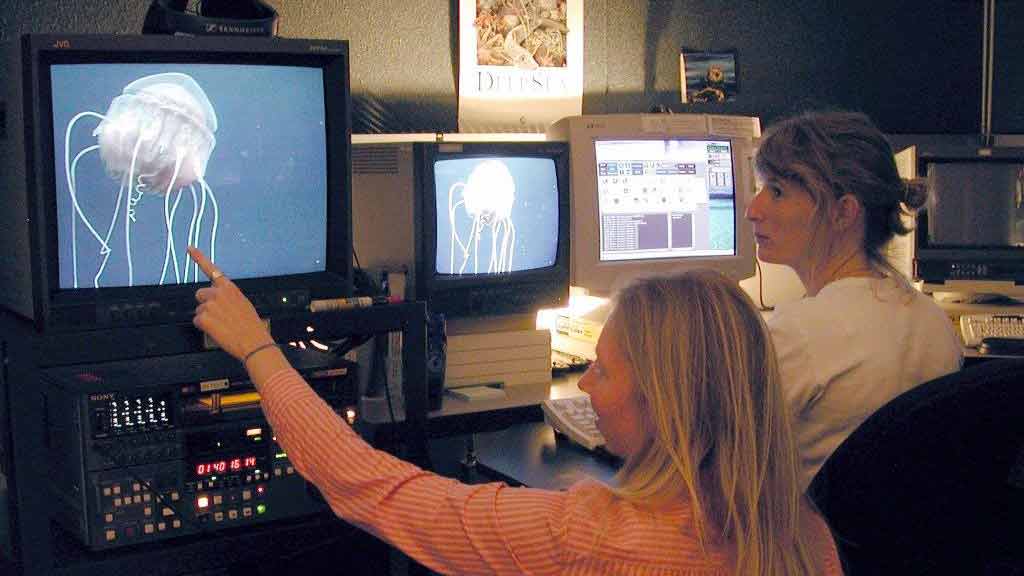

Inside MBARI’s Video Lab. (Photo by MBARI)

Staff members analyze it, frame by frame, identifying all the animals in the video along with details about the environment in which they live. The team has made 6.5 million observations over a 30-year period, logging 25,000 hours. That’s equivalent to watching TV for three years, 24 hours, 7 days a week!

On every dive, the team says they identify a creature they have never seen before. The Video Lab also has a large online following: A rare anglerfish, captured on MBARI cameras in 2014, has gotten 15 million views on YouTube.

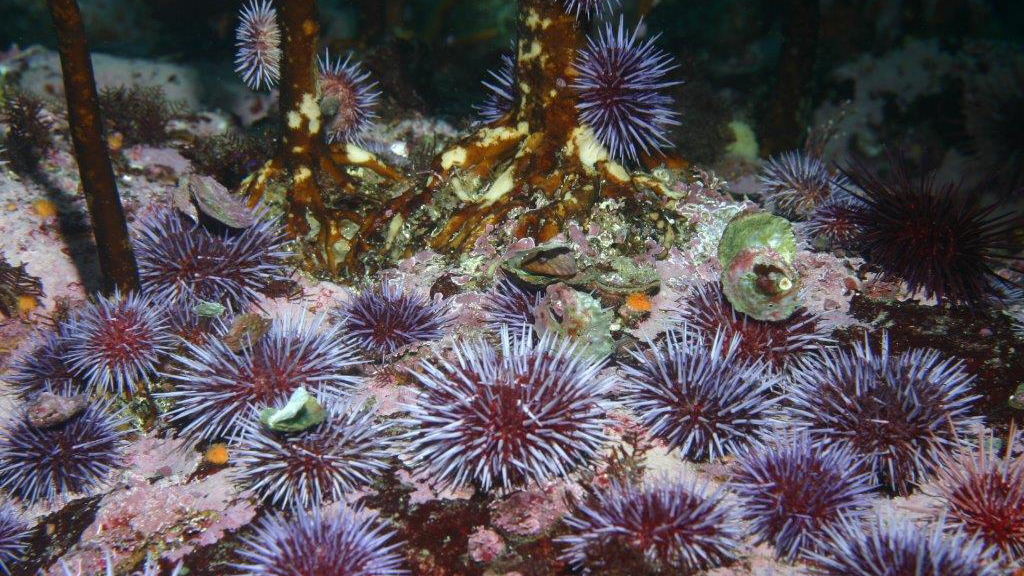

On a visit on the Bay, we saw scientists plunging into the waters. Their mission was to document the kelp forests on the ocean floor and figure out why they’re decreasing in numbers. One suspicion is that the exploding urchin population is the cause. Others point to climate change and warming waters. It can also be a combination of both.

To those I met who dedicate much of their lives to studying marine life, they say you have to know what’s out in the ocean in order to save it. Some express hope that their work will encourage people to be as fascinated with the oceans (and their importance to our life here on earth) as they are with space exploration.

Saving the oceans is a tall order, as they face increasing threats, both natural and man-made. To visually see how they are impacting the earth, EarthTime is a good source.

MBARI’s underwater ROV. (Photo by the National Press Foundation)

It was developed by a professor at Carnegie Mellon University and uses massive amounts of data from established governmental and non-governmental agencies. Instead of presenting a dry litany of numbers, EarthTime transforms the data into highly interactive visuals.

Among the graphics presented to us during one discussion was one showing bleaching of coral reefs worldwide. This is available to the public, free of charge. The demonstration of this invaluable tool highly impressed me and my journalists. We didn’t know the tool even existed. And it’s often hard to impress journalists.

Among the many man-made threats is also noise pollution. Marine species, like many animals, are sensitive to sounds as they serve as signals for basic functions like feeding and mating.

One disruption comes from “seal bombs.” They’re small explosive devices used to scare away sea lions and seals from preying on catch in fishing nets. Some reports have shown that seal bombs can impact whales and dolphins by damaging their bones and muscles.

Sea urchins in Monterey Bay. (Photo by NOAA)

Seafood from slaves

Among the most poignant speakers during the fellowship was Martha Mendoza, a reporter for the Associated Press. Her investigative story, “Seafood from Slaves,” won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for public service. For more than a year, she was part of a team of journalists who traveled to a remote island in Indonesia and documented how a small group of fishermen from Myanmar were held as forced labor.

Mendoza discussed one big red flag that made her journalistic instincts kick into high-gear: fishermen who would never get off the boat as they were constantly under the control of their captains.

They also tracked the complex fish supply chain of the fishermens’ catch using satellite imagery and websites tracking boat and trade movements. After an exhaustive investigation, the team discovered that the fish caught from this labor ended up in major U.S. supermarkets and restaurants.

Mendoza’s story led to the release of thousands of other enslaved fishermen and tougher regulations by the U.S. government.

Regulating Waters

Frances Kuo during the NPF fellowship for journalists.

The scope and complexity of ocean regulations can make your head spin. When you’re trying to monitor thousands of shipments of fish, things will fall through the cracks.

When it comes to international waters, regional fishery management organizations (17 exist currently around the world) oversee regulations regarding taking fish out of the ocean. Problem is, they were established after World War II, when there wasn’t much forethought to the threat of overfishing. And with several countries involved with competing interests, it can be difficult to reach consensus.

“They’re not working well,” said Amanda Nickson, Director of International Fisheries at Pew Charitable Trusts. “We’re only at the beginning of fixing the problem.”

Leon Panetta at Panetta Institute for Public Policy. (Photo by National Press Foundation)

Trying to fix the problem is something that has defined Leon Panetta’s illustrious career as a former Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, U.S. Defense Secretary, and Presidential Chief of Staff. As a native of Monterey, Panetta grew up with the ocean, and his grandfather was a fisherman.

Panetta established the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Legislation bars any construction, offshore drilling and other actions that threaten Monterey Bay. Panetta calls it his proudest moment as a U.S. Congressman.

Bridging gaps outside of the U.S. Capitol, Panetta also works to unite fishermen and environmentalists. Both sides can have competing interests, but Panetta believes that once you get them in a room and discussing the issues, consensus can be reached.

Panetta expressed some pessimism about the current partisan divide in Washington, and said what is needed is leadership on this issue, “a Teddy Roosevelt of the oceans.”

What also would help, Panetta added, is more awareness about the oceans and how important they are to our daily lives.

“There’s a tendency to take our oceans for granted, as if they’ll take care of themselves,” he said.

A bony fish known as mola mola swims at Monterey Bay Aquarium. (Photo by Frances Kuo)

What can you do?

Not all of us can be Leon Panettas, Martha Mendozas or MBARI scientists. So what role can us public citizens play to save the oceans which make up more than 70 percent of the surface of our planet?

The Monterey Bay Aquarium, one of the world’s largest, has some ideas. The theme of sustainability is a driving mission at the Aquarium – all the way to the dinner plate.

We were the guests of honor for a unique meal, presented at tables set up in front of a large water tank full of green sea turtles, sharks and mola molas, a funny-looking fish with large eyes, small mouths, and truncated tails.

The Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. (Photo by MBARI)

The chef, Matthew Beaudin, talked about how our dinner was literally the catch of the day. Despite his lack of “sea legs,” he had caught the rockfish of our main entrée alongside our Italian fish stew of shrimp and clams.

Beaudin is part of the Seafood Watch Blue Ribbon Task Force, a group of chefs and culinarians from across the United States recognized for their commitment to sustainable seafood and a healthy ocean.

I knew that evening where my dinner came from, but what about the next time I eat out? The Aquarium has launched the Seafood Watch app that contains information about businesses that serve sustainable seafood and which seafood is safe to eat.

It allows the public to be more informed about what they are consuming.

It’s easy to be seduced by the beauty of Monterey Bay. If I had visited simply as a tourist, I would be seeing everything from the surface. But this experience opened my eyes, that to keep the beauty of the oceans, we all have a role to protect them.

Frances Kuo is a CGTN America correspondent and producer.

CGTN America

CGTN America