While segregation was declared unconstitutional in 1954, it would take years for white schools to integrate. For Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, that day was set for Sept. 4, 1957.

Nine Black students were due to integrate the first high school in a major southern city amid public outcry from segregationists – including the governor of Arkansas.

Governor Orval Faubuseven had even called up the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the students from entering the school, saying it posed a risk of rioting and breaching the peace.

On the first day of school, hundreds of segregationists had gathered to harass and obstruct the Black students, who would become known as the Little Rock Nine. Civil rights organizers had told them to arrive with their parents and meet as a group so they could go in the school’s back entrance together, but they were turned away by the Arkansas National Guard.

Fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Eckford did not get the message to meet, and arrived alone at the front entrance of the school. She was immediately surrounded by a mob of segregationists as she walked to guards at the entranced of the school.

The Little Rock Nine stand with Journalist Daisy Bates (back row, second from right). (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy)

Eckford recounted the day in a 1998 interview with the Guardian newspaper.

“I walked up to the guard who had let the white students in. He too didn’t move. When I tried to squeeze past him, he raised his bayonet and then the other guards moved in and they raised their bayonets. They glared at me with a mean look and I was very frightened and didn’t know what to do,” she said. “I turned around and the crowd came toward me. They moved closer and closer. Somebody started yelling, ‘Lynch her! Lynch her!'”

Television and newspaper reporters, including Arkansas Democrat Photographer Will Counts, captured the mob harassing Eckford. Counts captured the above image of a white student, Hazel Bryan Massery, shouting “Go home, (n-word)! Go back to Africa” at Eckford.

That photo would be shared across the world and give international attention to the struggle to integrate U.S. schools.

Eckford saw a nearby bus bench and walked to it thinking it would give her some form of safety.

“I sat down and the mob crowded up and began shouting all over again. Someone hollered, ‘Drag her over to this tree! Let’s take care of that (N-word).’ Just then a white man sat down beside me, put his arm around me and patted my shoulder. He raised my chin and said, ‘Don’t let them see you cry,'” Eckford said in the Guardian interview.

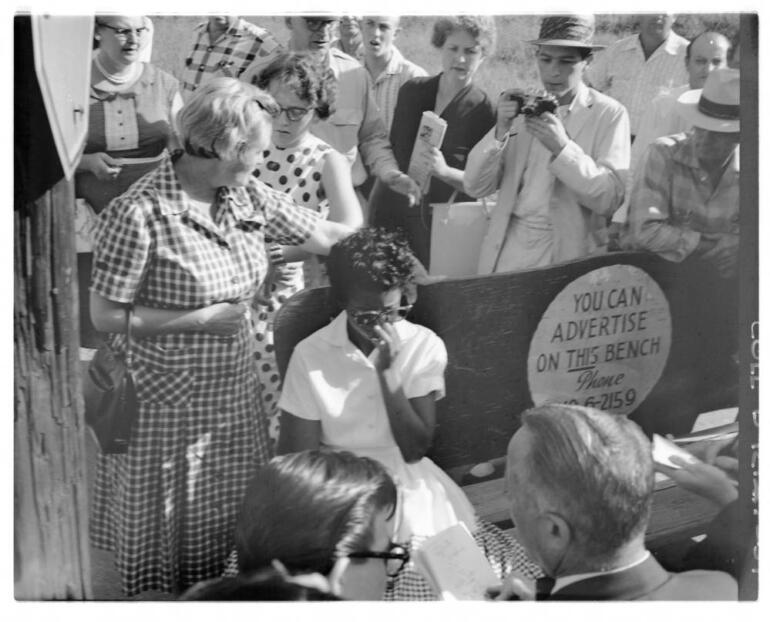

The man was Benjamin Fine, a reporter for the New York Times, who had a daughter around Eckford’s age. Soon Grace Lorch, a white civil rights activist and teacher stood up for Eckford and escorted her onto a city bus to safety.

Elizabeth Eckford with Grace Lorch in 1957. (Raymond Preddy/University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture)

The school district later condemned the governor’s actions and President Dwight Eisenhower asked the governor to withdraw the troops, but chose not to take any federal action until two weeks later, when the Little Rock Nine attempted to integrate again.

With a police escort, the Black students entered the school on Sept. 23. That day an even larger white mob had gathered and were able to trespass into the school. The Black students were taken to the principle’s office and then evacuated for safety.

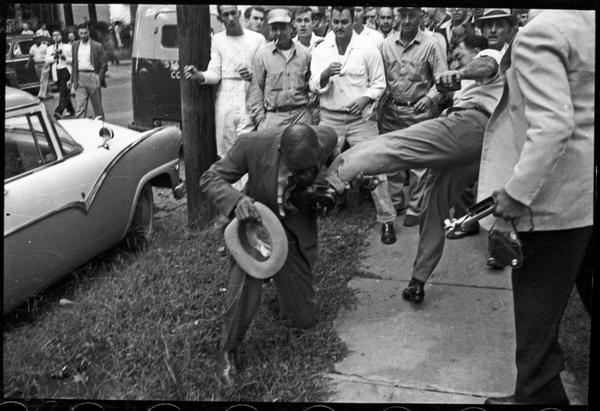

Outside, a group of white segregationist attacked and beat L. Alex Wilson, a Black reporter Memphis Tri-State Defender who was covering the story. One person jumped on his back and choked him, and another man hit him on the head with a brick, causing an injury that likely shortened his life. He died three years later at the age of 51.

Journalist Alex Wilson was beaten on September 23, 1957 while covering the Little Rock Nine and desegregation in Arkansas. (Will Counts, IU Archives)

The image of Wilson’s attack, also taken by Will Counts, and a telegram from the mayor of Little Rock urging presidential intervention prompted Eisenhower to finally use the Insurrection Act to send federal troops to Arkansas.

On Sept. 24, He ordered the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army to Little Rock and federalized the entire Arkansas National Guard. The troops were stationed there for the whole school year, but the Little Rock Nine still faced harassment and violence from White students. Eckford was thrown down a flight of stairs, for example. And another student Melba Pattillo Beals had acid thrown into her eyes and recalls being trapped in a bathroom stall while White students dropped pieces of burning paper on her from above.

Faubus continued to fight desegregation. After failing to delay the desegregation order, he signed acts to close all public high schools. While most white students found schooling with private schools and at other schools in the state, only about half of the Black students were able to get an education that year. The 1958-59 school year was known as “The Lost Year”.

In 1999 then President Bill Clinton presented the Little Rock Nine with the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award given by Congress to people who have provided outstanding service to the country.

Eckford never graduated from Central High School and ended up taking correspondence and night courses for her diploma. She enlisted in the army and later served as a probation officer. As she got older, she was diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder.

The white student in the iconic photo, Hazel Bryan Massery, left school at 17 when she married. In the years since that photo, her views on desegregation had changed, writes Author David Margolick in his book “Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock”.

Massery realized that her children would one day see her as the snarling girl in history books and in 1963 she called Eckford to apologize. Eckford accepted and the two didn’t speak again for decades.

Massery later got involved in peace activism and social work.

“She taught mothering skills to unmarried black women, and took underprivileged black teenagers on field trips. She frequented the black history section at the local Barnes & Noble, buying books by Cornel West and Shelby Steele and the companion volume to Eyes on the Prize,” Margolick writes.

“She read David Shipler’s study of black-white relations in America, A Country of Strangers, a book Elizabeth herself had helped inspire.”

In 1997, on the 40th anniversary of Central High School’s desegregation, Journalist Will Counts arranged for the two women to meet again for another photograph at the school. That year they also made speeches together at a reconciliation rally. The photograph of the two women decades later would later become a poster promoting racial healing.

The meeting sparked an actual friendship, Margolick writes.

Book cover for “Elizabeth and Hazel: Two women of Little Rock”.

“They went to flower shows together, bought fabrics together, took mineral baths and massages together, appeared in documentaries and before school groups together. Since Elizabeth had never learned to drive, Hazel joked that she had become Elizabeth’s chauffeur,” Margolick writes.

The two women even took a months-long racial healing seminar together discussing race relations.

But the close time they spent together led to hard realizations for both women, and by 2000 they had stopped being friends.

Eckford told Margolick that she felt Massery “wanted me to be cured and be over it and for this not to go on… She wanted me to be less uncomfortable so that she wouldn’t feel responsible anymore.”

When asked what she felt after seeing the photograph Massery responded that she was “just hamming it up and being recognized, getting attention” and that it wasn’t worth remembering.

But Eckford said that she learned that Massery had had weekly contact with the students on a local dance show “and she was part of an organized group that attacked us physically in the school,” Eckford told NPR.

Meanwhile Massery felt like she was under attack.

When the poster of the two women was set for a second printing, Eckford asked for a quote to the picture in the form of a sticker that read: “True reconciliation can occur only when we honestly acknowledge our painful, but shared, past.” – Elizabeth Eckford.

That confused Massery who thought she was doing just that, Margolick writes.

“She’d have liked to have had her own sticker, one that said, ‘True reconciliation can occur only when we honestly let go of resentment and hatred, and move forward,'” Margolick added.

The story of these two women, bound by two photographs taken 40 years apart, is now used to illustrate the challenges in overcoming the painful history of racism in the United States.

CGTN America

CGTN America

Elizabeth Eckford after she tried and was blocked from entering Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Hazel Bryan Massery is seen shouting at her from behind. (Will Counts Collection: Indiana University Archives)

Elizabeth Eckford after she tried and was blocked from entering Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Hazel Bryan Massery is seen shouting at her from behind. (Will Counts Collection: Indiana University Archives)