There are moments that make you realize the existence of God — or if you find that problematic — some greater, higher, or otherworldly power. Those moments can draw out a multitude of emotions from us: fear, awe, love, peace, and contentment

For me, it’s usually when I see an expression of beauty — whether it be in nature or something man-made like art or music. It makes you glad to be alive and lets you behold the world around you in awe.

Kogonada’s “Columbus” has that effect on me. This may seem hyperbole, but the film is closer to a religious experience than a movie seen in a theater. The South Korean born and U.S.-Midwest-raised director who uses the name Kogonada began his career as a video essayist and this is his first feature film.

Ahmad Coo is a producer and copy editor for the Global Business show on CGTN America. His analysis represents his views alone.

The plot of “Colombus” is secondary to its arresting cinematography, but both work in harmony to create the film’s overall atmospheric feel. The movie revolves around two characters, Jin played by John Cho, and Casey who’s played luminously by Haley Lu Richardson.

An emergency helps bring the two together, namely Jin’s father falling ill. It’s serious enough that Jin must put his life on pause in South Korea and fly to Columbus to be with him.

Both characters’ lives revolve around architecture. Jin’s father is a giant in the field, and a prominent academic. Casey is a precocious expert on architecture and a very knowledgeable tour guide. She’s a self-described architecture nerd and has a reverence for her hometown’s most prominent buildings. Columbus, Indiana is apparently a Mecca of architecture in the United States.

Their paths cross early in the movie, and they immediately recognize the kindred spirit in each other. Casey learns that Jin is the son of one of her biggest architecture heroes. Jin is smitten with her intelligence and frankness and they quickly develop a deep intimate friendship.

Both their lives are in stasis: Jin has to take an indefinite leave from his job and stay in Columbus to tend to his father. Casey is in a similar fix, she’s become her mother’s keeper, trying to make sure that she doesn’t date abusive men and stay off crystal meth.

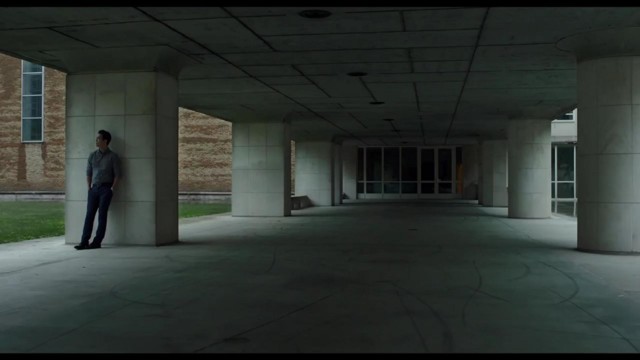

Casey (Richardson) in “Columbus” Courtesy: Superlative Films

Given Casey’s difficult life circumstances, she could’ve easily given in to despair. She tells Jin about how in her early teens, she almost gave up on life and her mother — who would disappear for weeks at a time on meth binges. At her lowest point, she finds herself in a hospital parking lot after bringing her mother to the emergency room to undergo detox. Caught up in her misery, she looks blankly at one of the buildings in the hospital complex. It was then when she ‘saw’ the building, when the structure revealed itself to her and opened her eyes to a hidden world.

Architecture becomes Casey’s savior. She realizes that aside from her love for it, she has a gift for design as well. Others see her potential and she’s offered an apprenticeship to one of the most prestigious architecture firms in the country. But her fear of her mother falling into another self-destructive cycle prevents her from embracing the opportunity. Like Jin, she’s caught in limbo.

Jin and Casey spend more time together and take walks around the Columbus, and slowly they become each other’s source of solace. She gives him the tour of the her city’s best known architectural gems, some of them designed by Eero Saarinen, the Finnish American best known for designing the iconic arch in St. Louis, Missouri.

Casey (Richardson) and Jin (Cho) in front of the Irwin Union Bank Courtesy: Superlative Films

At first, Jin doesn’t really understand Casey’s love for architecture, especially since he grew up with an overbearing father whose profession led him to ignore and neglect everything in his life, including his son. It’s obvious that Jin’s father left him with psychic wounds that would never heal. At one point during their many conversations, Jin tells Casey: “Sometimes you grow up around something, and it feels like nothing.”

But it’s Casey who slowly opens Jin’s eyes to the possibilities of architecture. And it’s through her eyes and words that we see the beauty of the city around them. Astonishingly, Kogonada’s skills of composition coupled with the collaboration with his cinematographer, he’s able to convey Casey’s sense of architectural awe on screen.

The buildings themselves become characters in the movie. Indeed, in some scenes they become the main attraction — with both Casey and Jin relegated to the background. Among them were Saarinen’s futuristic Northern Christian Church, the Irwin Union Bank, the Miller House, and I.M. Pei’s Cleo Rogers Memorial Library.

It’s hard to recreate the film’s use of characters and architecture in establishing the feel of the movie in words, but the closest thing I can compare to the style in “Columbus” is the American art movement known as precisionism that was born in the 1920s and 1930s. It’s a branch of modernism that took its inspiration from the rapid industrialization of the United States at the turn of the century. Some of the most prominent names in American modern art come from that era. For me, it’s Charles Sheeler and George Ault who stand out the most.

“Amoskeag Mills 2” (1948) by Charles Sheeler at Crystal Bridges Art Museum Courtesy: Mudangel

Precisionism is one of my favorite American art forms, it conveys a sense of isolation, loneliness and beauty, without having to rely on the human form, much like Kogonada’s style. Sheeler painted a lot of buildings and structures without the presence of any people, but still somehow imbued it with real soul. It’s the elevation of a desolate structure into the realm of spirituality. Kogonada’s film is an iteration of that theme.

Kogonada also infuses his work with a style developed by legendary Japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu. I wasn’t surprised to learn that Kogonada was most influenced by Ozu’s works. His assumed name is a play on Kogo Noda, Ozu’s longtime screenwriting partner. He uses many of Ozu’s techniques — the composition of scenes, pacing, lack of camera movement, and the placing of the film’s characters in space (and refusing to let them move around or if they do, the camera doesn’t follow them). With “Columbus”, Kogonada has become a worthy heir to the Ozu style.

Jin (Cho) contemplating life in “Columbus” Courtesy: Superlative Films

Ozu’s influence is also apparent in Kogonada’s treatment of the film and its plot. Instead of relying heavily on dialogue, he uses words sparingly, forcing the viewer to focus on the image to drive the story forward. In the last few scenes of “Columbus”, it becomes a really quiet film. In place of dialogue, Kogonada shows us again the city’s ethereal architecture — switching from building to building to highlight the importance of looking beyond our limited view of life around us.

Just like Ozu’s later films, the works of neorealist filmmakers, and the precisionist painters, Kogonada’s masterpiece has a special place in my heart. During my viewing, not once did I think of the ugliness of the news cycle, and yet it didn’t offer a way to disconnect from reality. Rather it opened the wider world to me and its hidden rhythms, whether it be in nature or buildings and structures made by those who aspired to lift the ordinary to the realm of the holy.

CGTN America

CGTN America

Casey (Haley Lu Richardson) and Jin (John Cho) standing in front of the Northern Christian Church in “Columbus” Photo by Elisha Christian Courtesy: Superlative Films

Casey (Haley Lu Richardson) and Jin (John Cho) standing in front of the Northern Christian Church in “Columbus” Photo by Elisha Christian Courtesy: Superlative Films