I became an American last week, a tortuous process that took more than two decades. There were 120 of us who took that oath. Most of us around the room projected joy and pride, while some looked dazed, and others seemed desperate. I think I exuded a mixture of the three.

As I was sitting in that cavernous courtroom in the nation’s capital, all I could think about was Gordon Hirabayashi, the activist whose family, along with tens of thousands of other Japanese American families, were placed in U.S. internment camps at the height of World War II.

Ahmad Coo is a producer and copy editor for the Global Business show on CGTN America. His analysis represents his views alone.

His life story had been bouncing around my head for a week before my oath, because I recently saw “Hold These Truths” — the excellent play about Hirabayashi’s life and activism, which is currently playing at Washington D.C.’s Arena Stage through April 8, 2018.

The title is from the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” Thomas Jefferson would declare on that historic document: “that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.”

Hirabayashi’s story is a sobering one, and it made me revisit all my doubts about becoming an American. We are all taught that this country is a land of freedom, where everyone, regardless of their background, is entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. In the more sanitized account of its history, the United States comes off as a true bastion of democracy and justice.

But the real world is a lot more complicated and “Hold These Truths” is a harsh reminder of that. Playwright Jeanne Sakata’s family was interned during the war and she wrote the play as a way to deal with her family’s painful past.

“There were deep psychic scars my father, aunts and uncles still carried from the experience of being imprisoned behind barbed wire as teenagers during World War II,” Sakata said in a interview in the Arena Stage’s playbill. “And as a third-generation Japanese American, I came to realize as an adult that if you don’t confront and work through trauma like that, you can easily grow up with that sense of inferiority, that sense of unspoken shame.”

Hirabayashi was raised with none of that toxic shame. He considered himself thoroughly American, with all the trappings that come with growing up in the U.S. Sakata’s play painted an idyllic childhood for him — that is until the U.S. entered World War II. That was when he realized he was “different”.

Japanese Americans were singled out by the government for being a threat to national security. By virtue of being descendants from a country that bombed Pearl Harbor, they could not be trusted to stay loyal to the United States. Nevermind that most Japanese Americans at that time were second-generation or third-generation immigrants. Nevermind that most of them had never even set foot in Japan.

Hirabayashi believed then that the persecution wouldn’t last and that the government would ultimately come to its senses and see his people as true Americans. But Franklin D. Roosevelt disabused him of that notion.

FDR signed an executive order removing 127,000 Japanese Americans from their homes all over the U.S. and forcibly relocated them to internment camps. The President did not consider Hirabayashi’s people as true Americans. It was a moment that shattered his view of the world. “The [U.S.] Constitution was meant to protect our rights,” the Hirabayashi character would say during the play. “But our faces… are the faces of the enemy.”

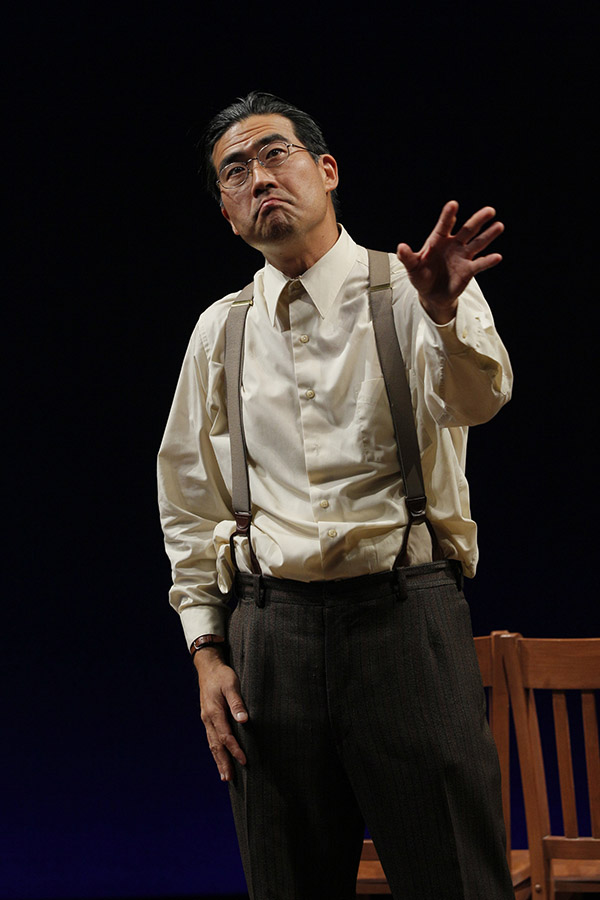

Ryun Yu as Gordon Hirabayashi in Hold These Truths, which runs February 23-April 8, 2018 at Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater. Photo by Chris Bennion for ACT-A Contemporary Theatre.

In Sakata’s one-man play, Hirabayashi is brought to life by Ryun Yu who pulls off one of the most chameleon-like performances I’ve seen on stage. It didn’t feel like it was just him and four chairs on a very spare stage. Yu became a sort of living marionette, taking on several personas and speaking an impressive array of voices and accents throughout the two-hour production.

Yu’s most impressive persona was his transformation into Gordon Hirabayashi. Yu masterfully played him as an earnest, idealistic, blazingly intelligent man who fought for his family and the countless Japanese Americans who were subject to persecution and internment. Ironically, Hirabayashi’s life is a very American one. His family came from Japan in search for a better life, to pursue their dreams, and remake their lives the way they saw fit.

It was ultimately Hirabayashi’s belief in this idea of America that convinced him to fight FDR’s decision to put Japanese Americans in virtual concentration camps in the desert. It was a battle that would go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Hirabayshi ultimately lost his case. The highest court in the land found that curfews placed on a minority group was constitutional when the U.S. was at war with a country where that minority group originated. However this decision was overturned in the 1980s in “coram nobis” proceedings — which are meant to correct a judgment upon discovery of a fundamental error that didn’t appear the original judgment’s proceedings.

“Ancestry,” Yu (as Hirabayashi) said, “is not a crime.”

The play could have easily been an embittered and hate-filled reaction to a sordid past. But Sakata’s script does it with wit, wicked humor, and most importantly, a sense of grace. There was anger and hurt but also hope, which “Hold These Truths” has in abundance.

It’s been 75 years since Japanese Americans were vilified and condemned by President Roosevelt without due process. One would think that such a betrayal would have made the U.S. government take a long and hard look at itself and its shameful history of treating immigrants. But taking a quick scan of headlines from the last year reveals that this country has a very bad collective memory.

Regardless of the disheartening developments in the U.S. under Trump, I take solace in Hirabayashi’s example. That’s why plays like “Hold These Truths” are even more crucial today. It reminds us that historical figures like Hirabayashi can serve as a beacon of justice and equality in such dark times.

Ryun Yu as Gordon Hirabayashi in Hold These Truths, which runs February 23-April 8, 2018 at Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater. Photo by Patrick Weishampel for Portland Center Stage.

I have to admit that when I walked into that D.C. District courtroom to take my oath as a U.S. citizen, I really questioned the wisdom of becoming an American, especially with its rapidly deteriorating political and social discourse.

But rather than contemplate the abyss of racism, I trained my thoughts on Gordon Hirabayashi and the struggles he had to go through and his eventual triumph. Somehow, that helped me feel a bit more at peace with my decision. It also helped that I was surrounded by with such diverse people hoping to become Americans.

During the ceremony, I sat next to an elderly woman from South Africa, and her joy was infectious. She waved her little American flag at the end of the oath, and gestured at me to do the same. I did, and somehow that small act of celebration made me — I dare say — a little hopeful for the future.

CGTN America

CGTN America

Ryun Yu as Gordon Hirabayashi in Hold These Truths, which runs February 23-April 8, 2018 at Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater. Photo by Patrick Weishampel for Portland Center Stage.

Ryun Yu as Gordon Hirabayashi in Hold These Truths, which runs February 23-April 8, 2018 at Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater. Photo by Patrick Weishampel for Portland Center Stage.