Part of the CGTN special series Rediscovering the New World

In a typical farmhouse from a 19th century Brazilian coffee plantation, the masters lived in the so-called Casa Grande – the Big House – while the slaves were confined to their quarters, called Senzalas.

In the Fazenda Bom Retiro – in the past, a large coffee plantation in São Paulo’s countryside – the Senzala was in the Big House’s basement. The current owner – who bought and restored the property in the early 1980s – also found some of the chains used to restrain the slaves that he kept on the walls of the Senzala.

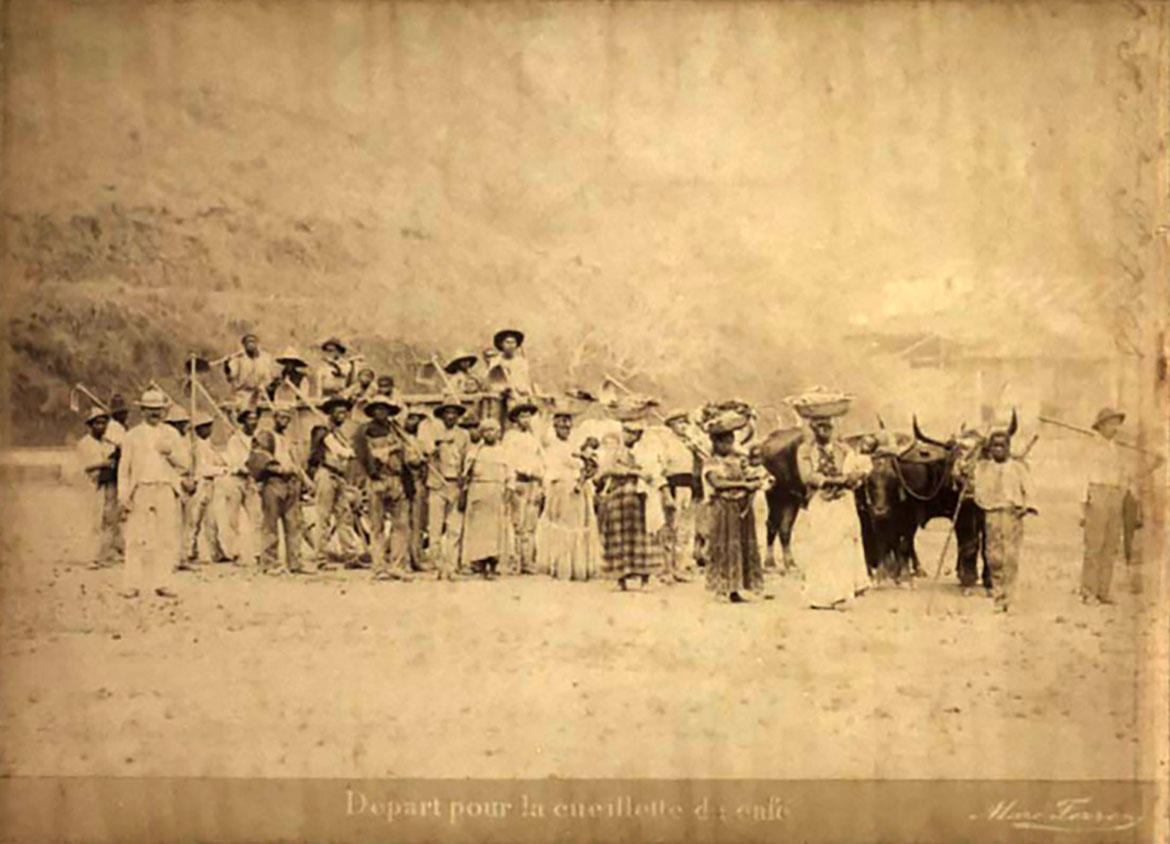

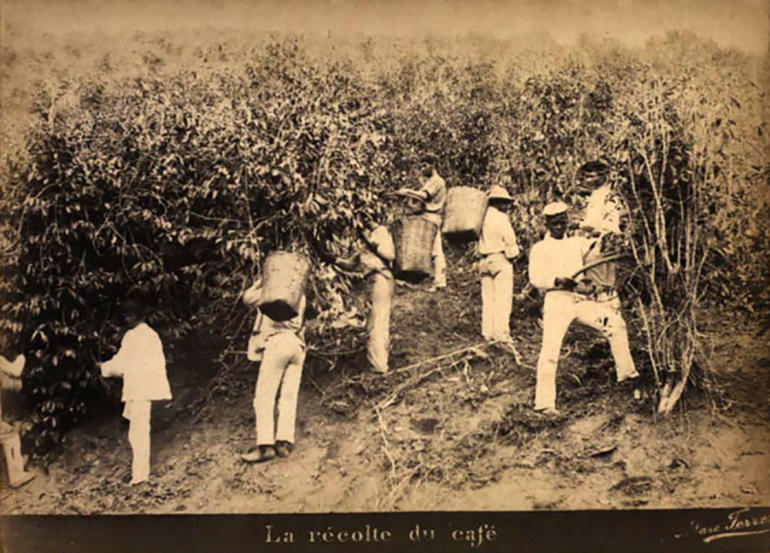

The use of slave labour was essential in the growth of Brazil’s coffee production, particularly from the 19th Century on. (PHOTO: Marc Ferrez / Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil)

Luizinho Santos also has a collection of documents from that period, salvaged right before they were about to be trashed in the small town of Paraibuna, in São Paulo’s countryside.

There are, for example, receipts for the payment of taxes on the purchase of a slave. An 1874 document states that farmer Guido de Andrade paid 30,000 Reis – the currency of Brazil at the time – for the purchase of slave Justiniano.

“We can’t hide these kind of things. It’s better to bring to the surface things that were hidden. For example, researching the story of my family I found out that when my great-great grandmother died, in the 1830s, her inventory included slaves owned by the family.”, said Santos.

“We cannot lie about the history. My family in the past condoned slavery. I don’t.”

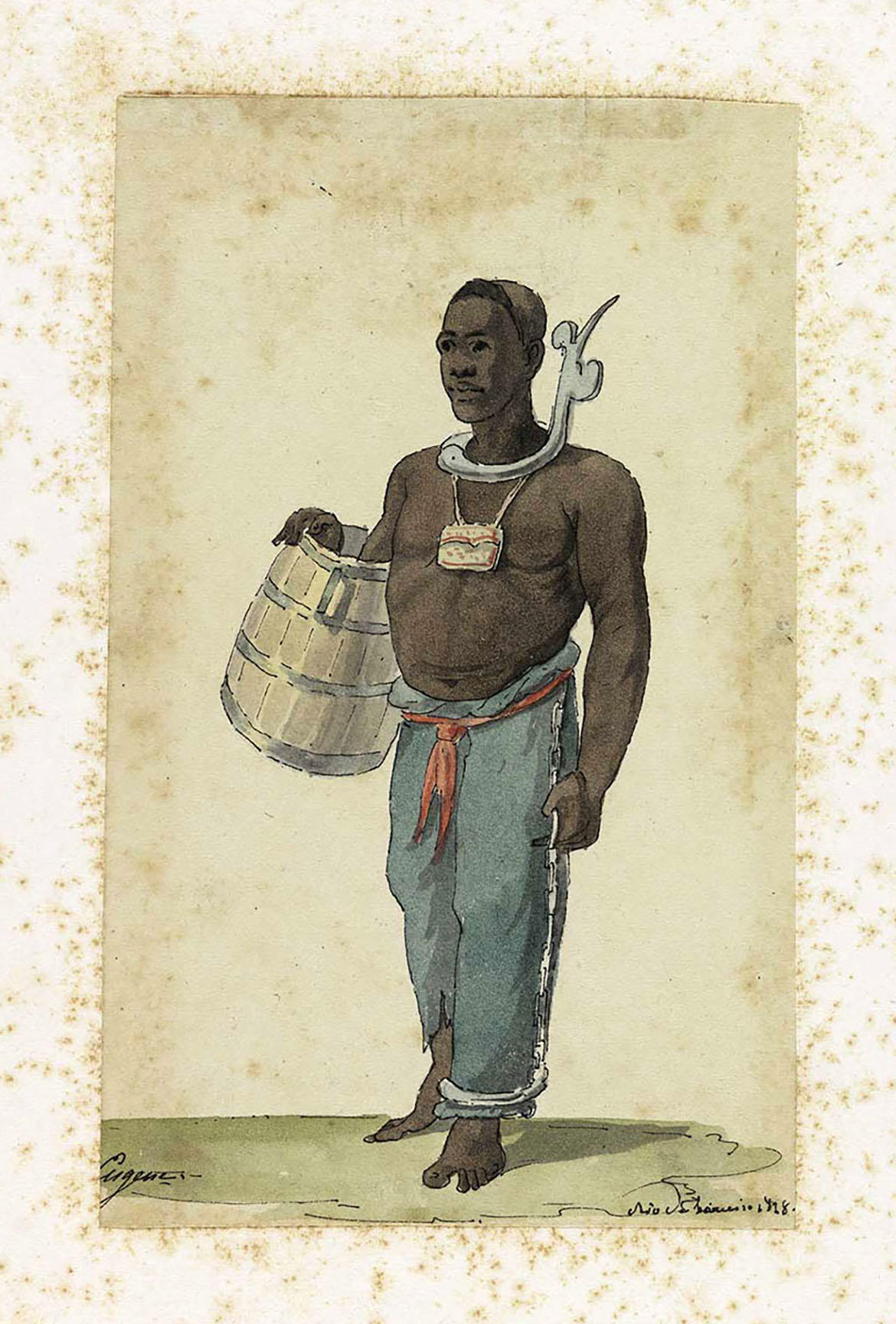

Captured runaway slaves were fit with metal hooks on their necks – the ‘canga’ – to limit their chances of scape, as shown in this 1828 drawing. (COURTESY: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil)

It is estimated that more than four million African slaves were brought to Brazil between the 16th and 19th centuries. It was the last Western country to abolish slavery in 1888. Over the years, thousands of slaves who escaped their masters established so-called Quilombo communities.

The biggest and best known of them was the Quilombo dos Palmares, led by Zumbi dos Palmares, depicted in the 1984 movie “Quilombo”. The day of Zumbi’s death, November 20th, is now officially marked as the day of Black Consciousness in Brazil.

Clip from the movie Quilombo

(Use settings on YouTube player for translation.)

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that Brazil began to recognize the rights of runaways’ descendants to Quilombo lands. In the Quilombo da Fazenda on the coast of São Paulo, a community of 80 families have been trying for years to get the permanent deeds for land already recognized as theirs.

They organize workshops to show outsiders – often university students – their traditional ways. -For example, how to build mud houses, or how to plant in the middle of the forest without having to clear it.

“Reaffirming our land rights and our culture is very important for us. We need to see guaranteed our right to housing and to have land for our crops because we want to continue living off our agriculture and not to rely on the cities and industries for our subsistence”, said Laura Braga, a community leader in the Quilombo da Fazenda

In this coffee plantation the masters live on the upper floor of the Casa Grande – the Big House – while the slaves were confined to their quarters in the basement, called “Senzalas”.

Brazil’s Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE, the country’s official stats bureau), African-Brazilians – either black or of mixed race – account for more than half of the population. And this segment’s slave roots are often cited as a primary reason for lagging behind whites, both economically and socially.

According to the most recent government data from 2015, 70 percent of African-Brazilians are considered poor or vulnerable, compared to about 46.3 percent of the white population. Also black families wages are, on average, 54 percent that of white families.

It is estimated that more than four million African slaves were brought to Brazil between the 16th and 19th centuries. It was the last Western country to abolish slavery – in 1888. (COURTESY: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil)

In education there are also significant differences. White Brazilians over age 15 have on average nine years of education; compared to just under seven and a half years for black Brazilians. And blacks are far more illiterate: more than nine million over the age of 15 – compared to 3.6 million whites.

In the Quilombo da Fazenda, descendants of runaway slaves show outsiders their traditional culture, like the construction of mud houses.

Uneafro, an NGO and black activist movement, works to help poorer Brazilians get an education and enter into university. Despite a quota system, black presence in higher education remains well below white enrollment.

“Brazil began with a story of 400 years of slavery. This has made deep marks in Brazilian society that are visible, even if often denied. That’s why black activist movements say reparation is needed on all levels.”, said one of the founders and coordinators of Uneafro, Douglas Belchior.

“The fact that the wealth in Brazil is concentrated on half a dozen millionaire families and the middle class, which is almost exclusively white, shows that we actually have a continuation of slavery, and had a fake abolition of slavery.”

Since slavery was abolished, African-Brazilians have been working to reclaim their identity and fight for social and economic equality. While there have been advances, it’s clear, 130 years later, there’s still much to do to close Brazil’s racial gap.

CGTN America

CGTN America

Photographer Marc Ferrez (1843-1923) travelled and photographed Brazil extensively in the 19th Century. His pictures of slaves and slave work are paramount in telling the history of this period in Brazil. (COURTESY: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil)

Photographer Marc Ferrez (1843-1923) travelled and photographed Brazil extensively in the 19th Century. His pictures of slaves and slave work are paramount in telling the history of this period in Brazil. (COURTESY: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil)